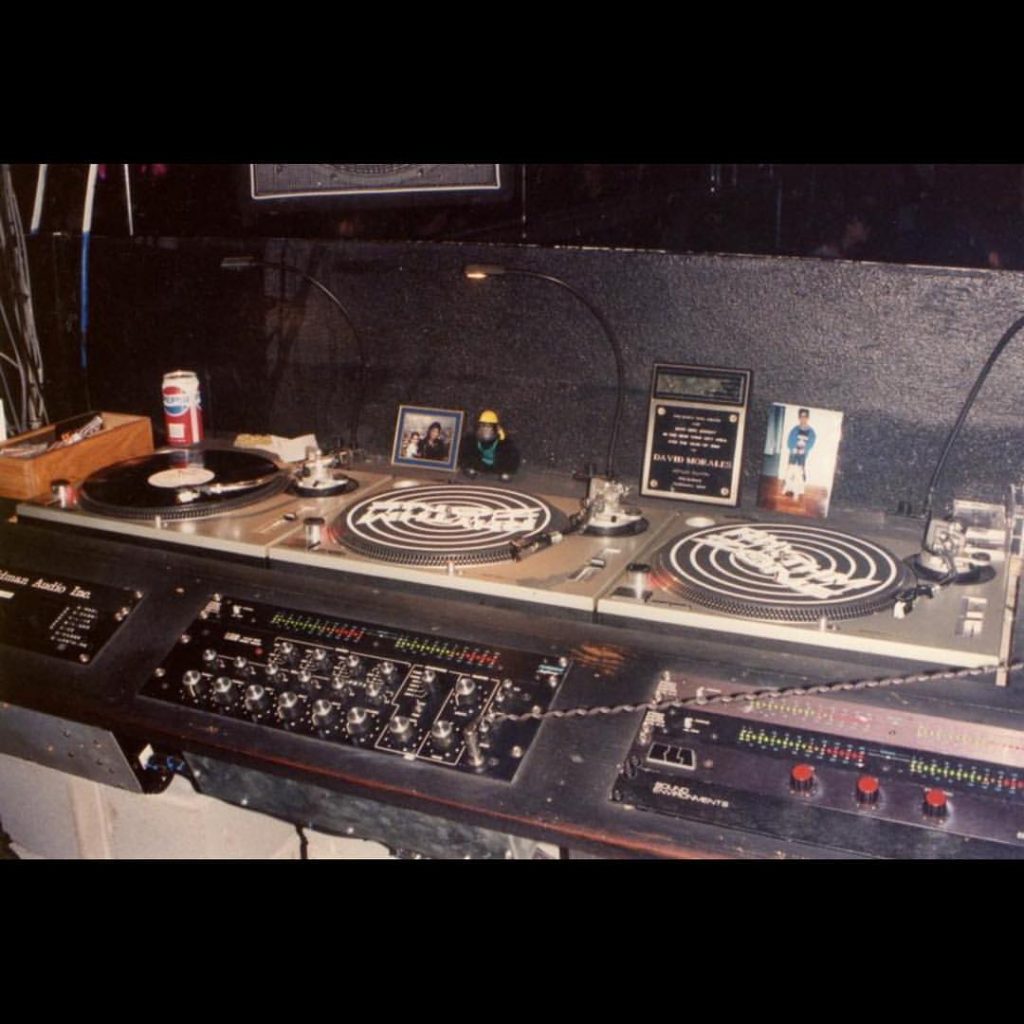

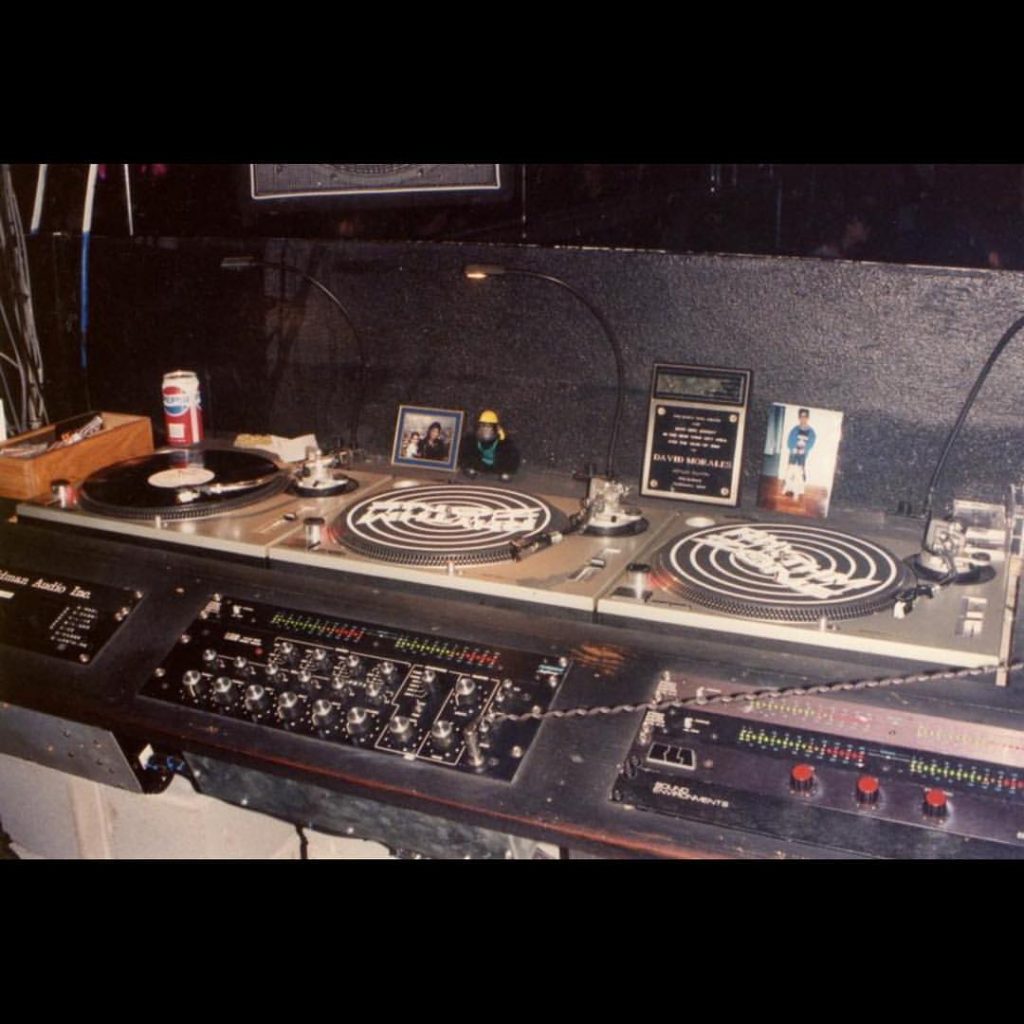

Posted: August 15th, 2016 | Author: Finn | Filed under: Features | Tags: David Morales, Groove, Interview | 6 Comments »

We should probably start at the very beginning. What were your baby steps as a DJ, what led you to being a DJ in the first place?

I think in the first place was the love for music. And I can remember when I was really, really young, with a babysitter, and we’re talking about the days of 45s. The first record that I actually remember and I was spinning was „Spinning Wheel“ by Blood, Sweat & Tears.

Good choice.

You know my family was from Puerto Rico and there was no American music in my house.

It was mostly Latin music?

Only Latin music. And we’re talking about Merengue, Salsa. Folk music from Puerto Rico. And I didn’t like it. And it’s funny because today I appreciate Latin music. Since I became a producer, now I appreciate Latin music for the production, the instrumentation, the musicians, because Latin music is not machine-made, not at all. So the first 45 that was in my house was “Jungle Fever” by Chakachas. My parents had this fucking 45 that was this erotic fucking record. And we’re talking about these stereos that were like these big fucking wooden consoles with the big tuner for the radio and the thing with the record where you put some records in the thing and it dropped one at a time and when it ended the thing drops. It must’ve been when I was about six or seven there was an illegal social club. You know I was living in the ghetto. So there were illegal social clubs that were like a black room, with day-glo spray paint, fluorescent lights to make the paint glow and they had a jukebox. And they’d play the music back then. „Mr. Big Stuff, who do you think you are“. It was all about the O’Jays and that kind of music. And I liked that. I used to sneak downstairs and such.

So when was that?

It was like the late sixties. Because I was born in ’62 so by ’70 that makes I was 8 years old. So it was before that because then I moved. Anyway, so fast forward the first 45 that I liked was the O’Jays. The first 45 I actually bought. And I remember playing that record I a hundred times a day. Putting the bullshit speaker we had in the house outside the window, we lived on the first floor. I played the record to death.

So you played it to the whole neighborhood?

The whole neighborhood. The only record I had really. So then when I graduated elementary school, I used to be into dancing, like the Jackson 5 they had “Dancing Machine”, there were The Temptations and Gladys Knight & The Pips and I liked that music. So then when we got into Junior High School – when I was like 13 years old, I had a girlfriend and we went out when the first DJs came on in the neighborhood, which was like the black DJs. I saw the first two Technics set up and a mixer in someone’s house. I was like “Wow! That’s interesting.” I saw somebody doing this non-stop disco mix and I never knew what that was all about. So, I used to hang out with all my friends. I was a dancer, we used to do all this what we now call breakdancing. We would do battles. So, I had one turntable and my friend would say “David, we hangin’ at my place” and I would play some music for us. So I just was a kid that sat by the stereo with the records and put on the tunes, one at a time. Because back then that’s what it was, you’d play one tune at a time. If it ended, the people clapped and you’d play the next tune. And it was all songs.

How did you proceed from there?

I was one of those kids that used to go to the record store even though I had no money. Just to look at the records. To walk by a store that sold turntables and a mixer and be like “one day, one day…” And I’m not working so I can’t afford to buy anything. My first mixer was a Mic mixer. 1977 there was a blackout in New York and there was a lot of stealing so I came across a radio shack little Mic mixer that I set up to make it work with two turntables. You had to turn two knobs at the same time and it was like mixing braille because there was no cueing. My one turntable had pitch control, the other one had none. I was too young to go to clubs, so I never saw a proper DJ mixing. I only saw people outside, we would have block parties and people would be mixing. And I was one of those kids that was just standing there, watching. The first time I went to a club I was 15 years old, it was Starship Discovery One. It was on 42nd street in Times Square, and we got in. We shouldn’t have got in, but you know it was the end of the club, I was 15 and I got in. The DJ had three Technics, the original 1200s, and a Bozak mixer. The booth was a bubble, and I had my nose at the fucking bubble and I was just mesmerized. The first time I actually played on a real mixer I went to a house party at my friend’s brothers apartment. And in those days, most of the DJs who were really playing were gay DJs. “San Francisco” by the Village People was the big record. But I was into The Trammps, I was into James Brown, I was into Eddie Kendricks, Jimmy Castor Bunch, “The Mexican”, Sam Records and of course Donna Summer and all this kind of stuff. So I went to this house party and he was the DJ, the first proper mixer I saw – this was before I went to that club. And it was a black mixer, it had two faders and it had cueing. So I see the DJ there, he’s using headphones to cue. So my friend says “D, you wanna play some music?” and I’m like “Yeah, sure.” I grabbed the headphones, put them on and I hit the cueing, because I was watching the guy, and I’m hearing some music and and I was like “Oh shit…” When I played at that party, I’d still play how I know how to play, which was braille. Intro, outro. And it wasn’t about mixing. All the new bars at that time were advertising nonstop disco mixes.

It was even mentioned on the record sleeves.

Yes. And all that meant was that the music never stopped. Because before the music used to stop before the next record came in. So now it was continuous. That worked, so here came the name nonstop disco mix. And then at that time all these records started coming out. The disco 45 record. At my junior high school prom “Doctor Love” by First Choice was big. And I remember the guy playing it about four times. So my first 12″ of course was “Ten Percent” by Double Exposure, on Salsoul. Another record that I played to death out the window.

You were still doing that?

I was still doing that. I used to live to just play music. I loved it. I would leave in the morning to go to school because my parents would go to work. I would buy a bag of weed, buy a quart of beer and I would go home. And you know in the old days we had all those buildings where you could really play loud music and I had these stupid double 18 boxes in my fucking bedroom. Before I’d take a piss, I turned my system up. My mother used to be like “turn that music down, turn that music down, turn that music down!”

Did you begin to play out around that time?

Yes, and playing at parties in those days meant you carried your records. Because you didn’t play for two hours, you played the whole party. And the thing is, if you owned 5000 records, you took 5000 records to the party. And in those days we carried milk crates. So here I am carrying eight to ten milk crates to a party. Getting in a car, getting a cab, you have all your friends who would help you going there, but when you’re leaving there is nobody to help. And you had to take the stereo system with you. So you carry the sound system and you carried your records. You took everything. It wasn’t like going somewhere and you just bring your records and they have everything. You had to take everything. I did parties for 15 dollars, for 25 dollars and you had to chase people down for your money.

What kind of events were you doing?

I played in clubs, I did Sweet Sixteens, I did weddings, I did corporate events. I did anything. I also did parties in high school. I would advertise a party, we would bring the sound system to some kid’s house, the parents left to go to work, we’d bring the sound system fast, and I would advertise free beer and free joints. Even 50 people is a lot of people in somebody’s apartment. Imagine we’d take over the apartment and it’s like 10 in the morning and we’d be fucking banging it, banging it, banging it — and we’d get out by 3 in the afternoon before the person’s parents come home. God knows the mess, whatever the case, baby. And in those days the sound system was in the living room, the DJ booth in the bedroom. No monitors, it was just bang bang bang. As I started doing parties at an apartment I used to charge a dollar to get in, decorate the apartment, put up balloons, and it just started with friends. Obviously still free beers, free joints, the whole thing. And like I said, I just loved the music, it was just everything for me. I wanted to play every single day. Even when I didn’t have the equipment, I knew friends that bought decks and a mixer and a small sound system for their house and they weren’t DJs and they used to say “David, come to my house and play music for me.” And I would just die to play, it was just everything for me. Read the rest of this entry »

Posted: February 15th, 2016 | Author: Finn | Filed under: Artikel | Tags: Groove, Radio | 4 Comments »

1977 bin ich acht Jahre alt, und ein Virtuose der Pausen-Taste meines BASF-Kassettenrekorders. Ich nehme vornehmlich Disco und Glam Rock-Ausläufer aus dem Radio auf. Werner Veigel ist der Yacht Rock-Don von NDR 2. Dann sagt Wolf-Dieter Stubel in der Internationalen Hitparade beim gleichen Sender angesäuert „God Save The Queen“ von den Sex Pistols an. Ich bin nicht überzeugt, aber das Musikprogramm wird in den folgenden Jahren wesentlich interessanter.

1981 habe ich das Nachtprogramm vom NDR entdeckt. Innerhalb kurzer Zeit nehme ich unfassbare Konzerte von Palais Schaumburg, Deutsch-Amerikanische Freundschaft und The Wirtschaftswunder auf.

1985 hat das Format-Radio Einzug gehalten, und es läuft gefühlt nur noch Phil Collins.

1985 wird Paul Baskerville schon wieder einen Sendeplatz beim NDR los, und spielt zum Abschied ausschließlich fantastische Musik aus seiner Heimatstadt Manchester.

1988 tanze ich seit zwei Jahren zu House in Hamburger und Kieler Clubs. Zum ersten Mal im Radio höre ich die Musik aber in einer mehrstündigen Live-Übertragung aus dem Hannoveraner Club Checkers.

1989 höre ich auf einer langen Autofahrt durch Frankreich eine beeindruckende Sendung namens „Ecstasy Club“. Aus Müsique forevör! Kurze Zeit später in Palma, auch nur noch House in der Playlist. Deutschland? Fehlanzeige.

1991 fahre ich durch Niedersachsen und kann endlich mal wieder John Peel auf BFBS hören. Er spielt dreimal hintereinander „Gypsy Woman“. Beim zweiten Mal summe ich mit.

1993 bin ich in London und mache im Hotelzimmer das Radio an. Noch am gleichen Tag kaufe ich auf dem Portobello Market zahlreiche Kassetten-Mitschnitte von amerikanischen DJs auf Kiss FM und englischen Jungle DJs. Ich will auch Piratensender.

1994 ist meine Freundin als Au Pair in Rom und schickt mir Tape-Mitschnitte von überragenden House-Shows des Senders Radio Centro Suono. Ich bin froh, dass es ihr so gut geht.

1994 startet Boris Dlugosch aus dem Hamburger Clubs Front seine Mixshow auf dem Jugendsender N-Joy. Jahre zu spät für das regelmäßige Club-Erlebnis im Radio, aber trotzdem höchst willkommen.

1995 zu Besuch in Berlin, letzte Love Parade auf dem Kurfürstendamm. Vor ihren Club-Gigs spielen eine Menge DJs im Radio. Ich kriege bis heute nicht raus, von wem der „When Doves Cry“-Bootleg ist, den alle zu haben scheinen.

1997 habe ich auch dieses Internet, arbeite mich systematisch durch die historischen Radioaufnahmen der Mix-Sektion der Deep House Page und rücke Kontexte zurecht. Ich brauche alles von WBLS und WBMX und komme mir aus nationaler Perspektive jetzt erst recht betrogen vor.

1999 verbrenne ich eine Menge Geld, um mit meinem AOL-Einwähltarif in Echtzeit ohne Buffer-Aussetzer das Set von Derrick Carter bei der Beta Lounge auf Kassette aufzunehmen und hasse den Real Player mehr als die CDU.

2001 habe ich auch dieses Breitband-Internet. Jetzt brauche ich alle historischen Radioshows, die ich kriegen kann. Kurze später finde ich heraus was ein monatliches Datenvolumen ist. Fies.

2002 habe ich auch diese Breitband-Flatrate und höre regelmäßig das Cybernetic Broadcast System. Dass Italo Disco, die heimlich verehrte Prollmusik meiner frühen Jugend, einmal derart hip sein würde, hätte ich niemals gedacht. Die anderen Bestandteile des Programms freuen mich aber auch.

2004 rotiert auf dem CBS der Acid House-Mix „Smileyville“, den ich mit einem Freund angefertigt habe. Result.

2005 sammle ich immer noch ausgiebig historische Radioshows und Club-Mitschnitte über gängige Suchmaschinen, aber jetzt kommen auch noch Podcasts hinzu. Ich verweigere mich iTunes und lade umständlich einzeln herunter.

2007 frage ich mich, was Steinski wohl so treibt und entdecke seine Themen-Sendungen auf WMFU. Ich höre begeistert Radio, als wären es wieder die 80er. Ein Moderator, ein Thema, Musik zum Thema. Vielleicht geht doch alles etwas zu schnell.

2007 erzählt mir Eric Wahlforss von seinem Start Up zum Austausch unter Musikern und gibt mir einen Voucher. Auf Soundcloud entdecke ich allerdings auch bereits reichlich Fremdeigentum. Mir schwant juristisches Konfliktpotential.

2007 gründe ich mit Freunden das Webzine D*ruffalo und dessen DJ-Exekutive, die D*ruffalo Hit Squad. Wir initiieren die Druffmix-Serie und peitschen nacheinander alles durch, was uns jemals musikalisch begeistert hat.

2010 schaue ich mir Theo Parrish im Boiler Room an, vom Schreibtisch aus. Ich frage mich wie viel bequemer alles noch werden wird, bevor es alle langweilt.

2011 Entnervt von den allwöchentlichen Gig-File-Tauschbörsen entscheiden Stefan Goldmann und ich den DJ-Mailout unseres Labels Macro einzustellen und stattdessen nur noch Radioshows zu bemustern. Wir recherchieren bis in die entlegensten Winkel und sind erstaunt, was es alles gibt.

2013 beginne ich nach diversen Gastauftritten bei terrestrischen und virtuellen Radiosendern über die Jahre bei dem neu gegründeten Berlin Community Radio meine monatliche Sendung „Hot Wax“. Eigentlich will ich nur präsentieren, was ich mir an neuer Musik von Hard Wax mitnehme, aber dann peitsche ich nacheinander alles durch, was mich jemals musikalisch begeistert hat.

2014 sitze ich auf einem Podium zum Thema Radio und Clubkultur. Monika Dietl hat eine Tüte mit Kassetten dabei, und spielt umwerfende Highlights ihrer Sendungen aus den 90ern vor. Nur Musik zu spielen, wie man es zur Zeit meistens macht, ist eben doch oft nicht alles.

2015 beugt sich Soundcloud dem Druck der Majors bezüglich Copyright-Verletzungen und löscht im Zuge auch die Accounts der Internet-Radiosender NTS, Red Light und Berlin Community Radio. Es folgt ein Exodus zu Mixcloud und anderen Plattformen, mit erheblichem Verlust an Reichweite.

2015 stelle ich aus Zeitmangel schweren Herzens „Hot Wax“ ein, nach 35 Sendungen.

2016 stelle ich zufällig fest, dass ich hundert Mitschnitte von Froggy & The Soul Mafia archiviert habe, obwohl mir die von ihnen gespielte Musik oft zu jazzfunkig und raregroovig ist, um mir das öfter anzuhören. Es ist mir aber egal. Ich weiß noch, wie es 1977 war.

Groove März/April 2016

Posted: May 10th, 2014 | Author: Finn | Filed under: Features | Tags: Danny Tenaglia, Groove, Interview | 1 Comment »

There are not many DJs who can look back on such a long and successful career as the 54 year old New Yorker Danny Tenaglia. Towards the end of last year he confirmed his extraordinary status once again during a rare visit to Germany where he played at Berlin’s Panorama Bar and Berghain on the same weekend. His enduring popularity can certainly be attributed to his often several hours long sets which still are packed with the most relevant new records of the current day. After all these years, Tenaglia still has his eyes on the future instead of the past. For this interview, though, he made an exception and looks back to the beginnings of his career.

Apparently you got hooked on dance music at a very young age. What led you into it? Were you coming from a musical household, or did you learn by yourself, by listening to the radio for example?

Growing up in the 1960s and 70s, we (mom, dad and four brothers) had always been around all kinds of music especially during big family gatherings, which were quite often. It was mostly my mom’s side as she was one of nine children. My dad only had one sister and his side was very reserved. All of my mom’s siblings were married and they all had children except for one aunt. This brought me 20 cousins, ten boys and ten girls, and when we all gathered together it was like an army! (laughs) We also had many second relatives and we were all born and raised in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, which is extremely popular these days since it is very close to Manhattan. Back then, Williamsburg was like a big version of Little Italy. When I visit Naples, Italy, it always reminds me so much of my childhood since Naples still looks exactly the same as it did 50 years ago. I can relate so well to the people there and on the island of Ischia as well.

I truly consider that this all started for me when I was only just a tiny fetus inside of what I call: “The Boom Womb Room!“ I guess I was always paying attention to beats, rhythms and melodies long before I knew what they even were. There was always music in my childhood. My mom’s younger sister Nancy was unable to have children of her own. However, she wound up becoming the most influential person in our entire family and had a wonderfully gifted voice. She always had music on. She bought records very often as there was coincidentally a record store right on our block. She even taught herself how to play piano and guitar by ear and this was initially how I learned to play as well.

Our family often had good reason to celebrate events like birthdays, weddings, anniversaries, family picnics, local catholic church festivals from the schools we all attended. I grew up listening to a lot of typical music that elderly Italian people would listen and dance to. Besides the obvious traditional music for dancing like the Tarantellas and the big band Benny Goodman swing music, there was plenty of the 50’s Doo Wop music as that’s what was big for them during this era. So I had no choice but too hear it all. Frank Sinatra, Barbra Streisand, The Beatles, Bossanovas and lots of soul music as well, Motown records particularly. Sometimes I think maybe my family were the ones to have invented karaoke? (laughs) There were many relatives who would love to take turns and sing their hearts out. And to end this deep question, it was most definitely my very dear aunt and godmother Nancy who taught me (and many of us) how to fully appreciate God’s gift of music, how to “feel it deep down in your soul“ and how by the changing of one simple chord that could be played with „great emotion“, it could bring upon unexplainable goose-bumps and quite often – even tears!

Were you aware that the music of those years was extraordinarily important, or was it just what was around then?

I definitely knew in my soul that it was meaningful. But I don’t think I realized how important it all was for me until I passed the age of ten and was realizing what type of music I was loving the most and only wanted to hear music I liked, as I was becoming sick and tired of the Frank Sinatra music and I was not a big fan of ballads and slow music until I eventually got heavily into soul music. I knew that I had possessed an incredibly deep passion for music since birth as relatives and friends would always make it obvious to my parents by saying things like: „One way or another this kid is going to be in the music business when he grows up“, because it basically was the only thing I displayed interest in. I had all kinds of little instruments and child record players, even reel to reel tape machines for kids. However, it did not truly hit me until I was about eleven or twelve when I was quickly finished with some music lessons because I was very young and did not like the discipline and how strict they were with me. They first took me for piano and then guitar lessons. I even attempted saxophone in seventh grade.

I had a great ear for music and which melodies worked together and which ones did not. Unfortunately, I did not posses „the gift“ of mastering an instrument, but I guess that ultimately it was a DJ mixer that became my main instrument of choice that I am stilling playing with today nearly 40 years later.

When you were still a kid, you got to know the prolific DJ Paul Casella, who played a part in turning you onto the profession. Can you tell how that shaped your decision to pursue a career in DJing?

Well, this is where I had then realized instantly at the mere age of twelve years old upon hearing an eight-track tape mixed continuously by Paul that I was somewhat mesmerized by because when I expected a song would end, then another would blend in. Sometimes harmonically on key and sometimes so perfectly that I kept asking my cousin who made this tape and how did he do this and how did he do that? Long story short, I called the telephone number on the 8-Track tape and Paul Casella happened to be nearby and came to our families grocery store and he brought us more 8-Track tapes. He wanted to meet me as he was amazed some little “little kid” was so impressed with him and the art of DJ-ing. I guess it was right around then in 1973 that I never showed much interest in anything else, including sports. I was not interested in any subjects in school, I was only interested in music, becoming a DJ, getting professional DJ equipment and getting gigs in big nightclubs and eventually this obviously led to my second career by nature which was producing music of my own, collecting synths, drum machines and various studio gear.

As you loved the music and heard about what was going down in the seminal clubs of that era, I guess you could not wait until you were old enough to go there yourself. Was it like you had imagined it to be? What kind of clubs could you already go to?

I was barely a teenager, so nightclubs were still a long way for me. But I can recall the anxiety and being extremely envious of my two older brothers, because they would go out often. But their interest was mainly to drink with their friends, meet girls and do what most guys from Brooklyn were doing in 1975. It wasn’t much different than what you can see in the movie Saturday Night Fever, including the fighting! However, when I was about 16 or 17 my older brothers would sometimes sneak me in to a few places which I will remember forever, and then they and other mature relatives and friends would basically chaperone me when I got my first job in a corner bar called The Miami Lounge in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. It was just a few blocks away from our house and the nights were starting at 9 pm, but my parents wanted me home by 1 am. The lounge is still there and it’s walking distance from the new and already famous club Output. The lounge looks exactly the same as it did in the 1970s but it’s now also a restaurant as well. I’m not sure of it’s current name, though.

You then had the privilege to witness some of the most celebrated clubs and DJs in New York like the Loft and the Paradise Garage and numerous others. Are the first impressions of those nights still vivid? Was it every bit as outstanding as it is described up to this day?

Yes, yes and yes! The Paradise Garage, The Loft, Inferno, Better Days, Starship Discovery 1, The Saint, Crisco Disco and many, many more that had come but now are sadly all gone! It’s a shame we don’t have much footage or even great photos of so many of these nostalgic parties and venues. There were so many options back then from all the way in Downtown Manhattan up to 57th Street and from East to West, seven nights a week. We had big venues, small venues, raw underground parties with no decor at all and obvious mega places like Studio 54 and Xenon. Then as the 80s came around we saw lots of changes with all kinds of theme parties at places like The Limelight, Area, Roxy and others. Read the rest of this entry »

Posted: October 21st, 2013 | Author: Finn | Filed under: Rezensionen | Tags: Groove, Larry Heard | No Comments »

Es ist bezeichnend, dass Larry Heard von den zahlreichen Plagiatsvorwürfen ausgespart blieb, mit denen sich die Chicago House-Pioniere nach den ersten Erfolgen gegenseitig überhäuften. Seine Musik war und blieb einzigartig. Es war offensichtlich, dass hier kein DJ mit schnellem Enthusiasmus Tracks zusammensetzte, die möglichst nächstes Wochenende das Warehouse oder die Music Box befeuern sollten. Hier hatte jemand eine Vision, die über die hektische Betriebsamkeit und die Effizienzprioritäten der Gründertage von House weit hinausging. Und es ist ebenso bezeichnend, dass dieses Album nur eine Zusammenstellung von vorher auf Singles veröffentlichten Tracks ist, und trotzdem ein ewiger Meilenstein geblieben ist, der bis heute als endgültige Referenz fortschwingt. Die fragile und reine Schönheit von Deep House-Prototypen wie „Can You Feel It“ und „Beyond The Stars“ ist nie wieder erreicht worden, und die psychedelische Rhythmik von „Washing Machine“oder „The Juice“ war auch schon dort, wo die anstehenden Wellen in Detroit, Chicago und überall sonst auf der Welt noch hinrollen würden. Blaupausen-Alert!

Groove 11/12 2013

Posted: March 16th, 2012 | Author: Finn | Filed under: Features | Tags: Boris Dlugosch, Front, Groove, Klaus Stockhausen, Phillip Clarke, Robert Johnson, Willi Prange | 1 Comment »

(printed on a Front T-shirt)

The typical club coordinates in Hamburg in the mid-1980s moved somewhere between mod culture and northern soul or post-punk and wave – in locations such as Kir – and disco preppydom at Trinity, Voilà and Stairways. The port of call was usually chosen by whether the evening plans focused on music and dancing, women or drinking. Some locations would satisfactorily cover all these needs, but in Hamburg it’s always been customary to frequent new locations as soon as an imbalance of these factors becomes too apparent. DJs usually didn’t do any mixing in those days and the music was often quite a wild potpourri of styles, so the nightlife crowd was used to only dancing to a couple of tracks and spending the rest of the night doing other things.

However, a little off the beaten track, near Berliner Tor, there was Front, a club Willi Prange opened in 1983. In 1984, Klaus Stockhausen from Cologne became the resident DJ and like his fellow DJs in others parts of town, he played a mixture of boogie, synthpop, electro, hi-energy and Italo. However, in the eyes of the rest of the city, Front soon had a special status. The main reason for that was probably that most of the guests were gay, that is if one can believe hearsay, who didn’t mind partying the weekend away so far-off from the usual Reeperbahn and Alster area haunts. On the other hand, what was perhaps even more deciding was Stockhausen, who was miles ahead of his colleagues in many ways. I first heard about his amazing DJ skills from one of my best friends, who was a few years older than me and had been frequenting Front since 1984. One evening he’d persuaded Stockhausen to sell him a set of live recordings on tape, for quite a lofty sum – well, the man certainly knew what he was worth.

When I heard the tapes for the first time, I was pretty stunned. I’d always had a weakness for all kinds of danceable music, but what you could do with it when you mix it was totally new to me then. I spotted certain parts of my record collection, but somehow it all sounded different, more energetic and more exciting. There were many instrumental versions, laced with sound effects, scratching and a cappella vocals. You could hear different records playing at the same time, sometimes for several minutes on end, or certain parts for just a few seconds. Most of the time I couldn’t even tell the tracks apart anymore, and I didn’t have a clue how he did it. Moreover, the choice of music was always both very stylish and adventurous. Must be mind-blowing to hear him perform live, I thought.

The nights at Front were already quite a steamy affair at that time, but things really took off at the end of 1985, when Tractor and later Rocco and Container Records started stocking the first house imports. In fact, I only really noticed house when “Jack Your Body” and “Love Can’t Turn Around” suddenly became hits in 1986, but I took an instant liking to it. It seemed like the perfect synthesis of all sorts of club styles, and yet it was also really basic and direct. A promising variation in the chronology of disco music, so to speak. And according to ear witnesses, house was monopolized as of day one at Front, even though there weren’t that many records you could buy, but whatever was available, you could hear it at Front. The European club landscape is admittedly too diverse and extensive to pinpoint where things were actually sparked off exactly, but if you take a look at the musical history books of other countries, Hamburg was in there damn early, without even making a big fuss about it. The regular weekend guests from England certainly seemed to have set out to the touristic wasteland on Heidenkampsweg with full intent to dance and were not there by chance.

The first time I was actually part of the bizarre queue that lined up in good time in front of the stairs leading down to the club was in early 1987. I was almost of age and a little tense. It seemed as if the cool guys around me could hardly wait to be let in by the grumpy moustached geezer who was in charge of the cellar door. The proud majority of the audience consisted of pretty boys in glamorous outfits and half-naked muscle-packed leather types, and there were plenty of them, later to be found on the dance floor, dancing and screaming their hearts out in delight. The club itself was anything but glamorous – “bare” would be putting it mildly. There was nothing on the walls apart from a few emergency exit signs on which the word “danger” blinked from time to time and intermittent slide projections of meaningless phrases like “I mean… is he…” or “…and suddenly…”. The dance floor was surrounded by low platforms with railings which – owing to the low ceiling – meant you were even closer to the nasty tweeter loudspeakers of the sound system that wasn’t exactly good, but it was very effective and, what’s more, very loud. The light-show merely consisted of different-coloured fluorescent tubes, sporadically lighting up the dark dance floor at incomprehensible intervals. And in contrast to other clubs in Hamburg at the time, it was very dark, not to mention the incredible fug of more or less naked bodies that was dripping from the ceiling or channelled back onto the street by the ventilation system, pouring out right next to the entrance as a thick cloud of steam, as if announcing to the outside world like the smoke at a papal conclave what levels of excess had been mutually reached that weekend.

Front was a place that you’d go to in order to dance, rather than to pose, although you could of course also do both if necessary, and wander from left to right, spellbound by the booming splendour. The atmosphere was extremely physical and highly sexed: the Front kids had designed their temple, paying reverence to hedonism with unconditional allegiance. In fact, nothing mattered as long as it was fun. If you left the dance floor, not that anyone would ever want to, the only distraction was a bar with a few benches, one floor down, whose drinks taps were tipped to the beat accompanied by the sounds of partying bar staff – often dressed in torero outfits. Other distractions included the notorious toilets, which were extraordinarily highly frequented and snubbed any notions of segregation of the sexes, as well as a pinball machine that never worked. The exuberance was deliberate, controlled from a DJ area which was very different to those in any other clubs in one respect: you couldn’t see the DJ. It was an elevated dark booth that you accessed through a door from the dance floor, and the DJ – whom you could only catch glimpses of – could look out through two tiny crenels. That had the effect that you concentrated on the music and sometimes it seemed as if it was coming from another world, although you were fully aware, of course, that the master of ceremonies responsible was something special, applauded with screams of delight on the dance floor. Clearly a renunciation of the elsewhere increasingly popular trend of hero-worshipping specific DJs – a trend that was ultimately the reason why Stockhausen laid down his headphones forever in 1991 to pursue an equally successful career as a fashion editor for well-known lifestyle magazines. I only found out many years later what he actually looked like, thanks to a series of photos in a city magazine, though it didn’t really matter anyway. The same went for his highly talented successor Boris Dlugosch, who became Stockhausen’s protégé as of 1986 and took over the baton after he left, directing the next era of the club just as stylishly – as did other DJs such as Michael Braune, Michi Lange, Sören Schnakenberg and Merve Japes. In time, more and more celebrities came, but were hardly taken any notice of.

These conditions didn’t change much in the years that followed. There were rituals like the quadraphonic test record that crackled away with the lights turned off, usually heralding in the final phase with a review of disco classics, though the Front’s sound system made even those sound like they’d been reborn in a ball of lightning. There were various wild and special events plus the annual birthday bash where, believe it or not, everything was turned one notch higher. Unforgotten is also the performance of an innocent busker who, on the outbreak of the first Gulf War, was engaged ad hoc on the high street and nervously played “Give Peace A Chance” on his guitar to an ecstatic audience.

In the developments of house music and all the various different styles emerging from it, Front served as a tough yardstick in the following years. First came the acid phase, which also conquered the rest of Hamburg in other new locations such as Opera House, Shag and Shangri-La, and the first wave of Detroit techno was welcomed with open arms. In those days, trips to clubs in other cities were often rather disappointing by comparison, and you soon looked forward to the next night out at home. In 1989 the New York hybrids of techno and house from Nu Groove and Strictly Rhythm followed, and the post-acid developments from Britain, such as Bleeps or Shut Up And Dance and 4hero, generally referred to as breakbeat techno back then, were also received to some acclaim. When techno started to increasingly define itself in terms of hardness as of ‘91, Front returned to its groove roots, leaving the speed-freaks to get on with it at locations like the first Unit. Overnight, garage and deep house were virtually mixed to new heights under the aegis of Dlugosch, without losing any of the easygoing dynamics on the dance floor: the delirious frenzy just happened to sound a little different now. Front embodied thrust and style and had brought its followers up on house to its best ability, which is why Hamburg never became much of a techno city compared to other metropolises. The club featured in Face, I-D and Tempo magazine as a world-class location and, with Dlugosch, was at least on a par with purely house and garage clubs in the USA and England, and was practically unrivalled on the continent for many years, which was underpinned by the fact that Front soon started to book big names from abroad. DJ Pierre slipped up on Wild Pitch and made up for it with acid meets garage; Mike Hitman Wilson botched up completely; Frankie Knuckles put a towel round his shoulders, placed a bottle of cognac and a desk fan in front of him and then set out to communicate just that; the Murk Boys were mutual love at first sight; and Derrick May didn’t want to stop.

But the first guests also offered insights into other scenes, which got more and more club-goers interested, and competition in Hamburg soared, generally using Front as the benchmark. The gay crowd felt increasingly more corned by prying eyes, and eventually the faces of the first generation gradually stopped coming and started going elsewhere. Not only the spirit of the pioneering age was waning but also the music began to lose its intensity. Even the 24-hour petrol station round the corner suddenly shut down. Nevertheless, like many others I felt privileged to have witnessed the emergence of house, happening live at such a special place that we all still carry in our hearts. At some point the show ran by itself and at other venues – as of ’94, I went there far less frequently, until I got a wake-up call in ‘97 when I suddenly heard about the farewell party. I preferred to remember it as it was in its heyday and decided not to go. Befitting for a truly legendary club, the deco was later auctioned like relics to the highest bidders. But I already had the perfect souvenir and it still adorns my door: the sign of the ladies’ toilets, mysteriously stuck to my T-shirt one Sunday afternoon when I woke up on the floor at a friend’s place still in my outfit from the night before. Those were the days. Klaus Stockhausen is still the best DJ I’ve ever heard and for me the club’s intensity is still unparalleled, minus a bit of sentimental glorification. It left a deep impression on me. Whenever I drive into Hamburg coming from Berlin, I always steal a glance at the Leder-Schüler building and hear music in my head. This used to be my playground.

Many thanks to Walter Fasshauer, Patrick Lazhar and Frank Ilgener.

R.I.P. Willi Prange and Phillip Clarke

Text translated by Carol Christine Stichel for the accompanying newspaper to the book Come On In My Kitchen – The Robert Johnson Book. Original German text here.

Posted: December 16th, 2011 | Author: Finn | Filed under: Artikel | Tags: Groove | No Comments »

Durch die Umwälzungen, die durch Downloads und digitales DJing ausgelöst wurden, rückte im letzten Jahr mehr und mehr eine Käuferschicht in den Vordergrund, die zwar immer befriedigt wurde, und befriedigt werden wollte, aber selten so direkt in der Peilung war: Sammler und Komplettisten. Man konnte sich als Künstler, Label und Vertrieb schon immer auf diese Konsumenten verlassen, wenn man Veröffentlichungen mit wie auch immer geartetem Mehrwert verkaufen wollte, doch nun schien es fast, als wäre man in Zeiten schwindender Erlöse aus physikalischen Tonträgern direkt auf sie angewiesen.

Vor allem am Discogs Marketplace, dem mittlerweile ausschlaggebenden Gebrauchtmarkt für elektronische Musik, ließen sich Entwicklungen verfolgen, die vorher zwar auch existierten, aber in schwächerer Ausprägung. In Zeiten des virtuellen Informationsüberflusses konnte man sich binnen kürzester Zeit mit dem nötigen Wissen ausstatten, um das jeweilige Sammelgebiet in Angriff zu nehmen, und dann war auch alles gleich verfügbar, denn es drängten weitaus mehr als zuvor ältere und neuere Second Hand-Platten in den Markt. DJs lösten ihre vorher digitalisierten Plattensammlungen auf, um sie danach gewinnbringend zu verkaufen, und viele neue Händler, von heftigen Verkaufspreisen für Raritäten angelockt, versuchten ihr Stück vom Kuchen abzubekommen. Folglich fiel der Preis für etliche vormals kaum erschwingliche Releases zusehends. Um da noch auf einen vernünftigen Schnitt zu kommen, musste man sich als Verkäufer auf ein Angebot spezialisieren, das entweder über Masse den Profit generiert, oder die Klasse anbieten, die eben noch nicht vom Preisverfall betroffen war. Also ältere Platten, die seit Jahren einfach immer selten und teuer waren und sein werden, und neuere Platten, die vom Release-Termin an einfach nur darauf ausgelegt waren, selten und teuer zu sein.

Die Produktionsseite stellte sich jedenfalls schnell auf die neuen Tendenzen ein. Den Boden bereitete eine Vielzahl von Wiederveröffentlichungen, entweder gewissenhaft lizensiert, ausgestattet und kuratiert, oder höchst windige und schnellgeschossene Bootlegs, und beider Release-Plan orientierte sich ziemlich präzise an Angebot und Nachfrage des Gebrauchtmarktes. Je rarer, je lukrativer. Erstaunlicherweise waren vor allem viele Bootlegs oft dicht dran am Preis der Originale, ohne das Original-Artwork, oder sogar das Original-Tracklisting bieten zu können, und verkauften sich trotzdem prächtig. Sei es Bequemlichkeit oder Kaufreflex, charakteristische Verhaltensweisen des Sammlerpublikums ließen sich nicht nur bestenfalls effektiv einkalkulieren, sie wurden auch schlimmstenfalls schamlos ausgenutzt.

In einer beachtlichen Anzahl von Vertriebsankündigungen fiel das Wort „limitiert“, ungeachtet der Tatsache, dass viele Platten ohnehin nicht mehr Auflage absetzen können, als sie limitieren. Das ist keine neue Strategie, und eine durchsichtige dazu, die aber immer noch oft funktioniert. Man hat mehr Plattformen und Kanäle zur Verfügung als je zuvor um Beschaffungshektik auszulösen und dem Käuferkreis zu versichern, er könne leer ausgehen, wenn er sich nicht sputet. Oft ist das tatsächlich der Fall, das ist prinzipiell seit jeher der Schnelllebigkeit der Clubmusik geschuldet, entsprechenden Risikokalkulationen, aber auch dem Bestreben, mit künstlicher Verknappung ein Sammlerobjekt zu kreieren. Künstler bzw. Label erhoffen sich Releases, die durch unbefriedigte Nachfrage gesucht sind und somit den Backkatalog aufwerten, der Käufer erhofft sich, im Besitz eines Sammlerobjektes zu sein, auf dessen zeitnahe Aufwertung sich spekulieren lässt. Tatsächlich steigen viele schwer erhältliche bzw. schwer erhältlich gemachte Platten rasant im Preis und lassen sich dann gewinnbringend wiederverkaufen. Diese Preise fallen aber ebenso rasant wieder, da muss man den Kurs sehr regelmäßig im Auge behalten.

Der stärkste Motor dieser Vorgänge ist natürlich der Kultstatus. Und hat sich ein Label oder ein Produzent mit entsprechendem Output diese Stellung erarbeitet, ist es zwar nicht zwingend, aber durchaus legitim, wenn sich das im Preis von Veröffentlichungen niederschlägt, sofern der Output diese Vorgehensweise auch über einen längeren Zeitraum rechtfertigt. Als Verbraucher muss man für sich selbst entscheiden, ob man bereit ist, für den Namen mit zu bezahlen, was dann auch einer Respektbekundung gleichkommt, oder ob sich dieser Name mit der Zeit verbraucht. Und da die Berichterstattung heutzutage eher mehr Nachschub an Namen braucht als früher, kann das schneller gehen als ursprünglich gedacht. Auf jeden Fall gilt auch hier, dass es mindestens genauso schwierig ist, einen Status zu erreichen, wie ihn zu behaupten. Wer konstant ein paar Euro mehr auf den Einkaufspreis aufschlägt, weil er sich seiner Fans sicher wähnt, muss auch entsprechend liefern, denn Sammler sind nicht nur schnell entflammt, sie kühlen auch schnell wieder ab, und sie sind potentiell nachtragend. Der Bogen lässt sich oft eine ganze Weile überspannen, aber dann ist nicht nur genug, sondern Schluss, und man kehrt meistens auch nicht zurück. Es gibt immer noch genug andere Fische im Teich.

Paradoxerweise ist der Mehrwert, den Vinyl-Releases als Abgrenzung zu Audiofiles bieten sollten, zum Problem geworden. Pop- und Szenestars sowie sonstige Veröffentlichende in Aufschwung, Stagnation oder Abschwung schließen die Tore von Beginn an über Auflage, Preis und verkomplizierte Verteilungen an ausgesuchte Läden, und Sekundärhändler multiplizieren die Anfangsgebote um ein Vielfaches. Alles oft bevor die Releases überhaupt wirklich in den Handel gekommen sind.

Und so mancher wird sich schon binnen kurzer Zeit fragen, ob die vorsichtshalber doppelt gekaufte limitierte Erstauflage mit Vollbildcover, das Poster, oder der unveröffentlichte Bonustrack den ganzen Hassel wert war. Wenn man nicht nur sowieso gar kein Cover hat, ein gestempeltes Label, und Musik, die eigentlich nicht die Qualität hat, in den Gegenwert hinein zu altern, den man ursprünglich angemessen bezahlt zu haben glaubte. Bis dann der nächste Hype losgetreten wird.

Groove 01/12

Posted: October 27th, 2010 | Author: Finn | Filed under: Features | Tags: DJ Harvey, Groove, Interview | 32 Comments »

You’ve been away for a quite a while now.

Yes, almost ten years since I left England. The reason was not by my design. I was enjoying America so much that I overstayed my visa. If I was to leave, I would have not been allowed back for another five or ten years and I was planning on making my life there. And only a year and a half ago I got married and applied for my green card. And I now have the green card, and my work visa and my right to travel and re-enter the States. So here I am, back in the world. I recently completed a big tour of Japan and I’m on a major tour of Europe right now.

You got married and still it took such a while to get your green card?

Well, actually the process is a lot quicker now than it used to be. From the time I put my application in it was actually only four months until the card came through. Since 9/11 the background check is a little more stringent, but the whole process is now centralized, instead of the department in Washington, and the department in Detroit and so on. There’s one computer, and if you fit the criteria then it’s all good.

So you spent all those years of your self-imposed exile just playing in the States?

Yes, but on a regular basis. America is a big place. And I have a regular circuit. Starting on the Northeast coast, Detroit, Chicago, New York City, Philadelphia, Washington, Miami, then skipping over to the other side, San Diego, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Boulder and Seattle. And that’s not even including Hawaii. So that’s plenty of work, even if I do that once every couple of months.

But your main bases are Hawaii, Los Angeles and New York City?

Basically yes. My most regular gigs would be there.

Would you say that these are also the cities where your music fits best? Is there a better scene for what you play?

Everywhere I play people come to hear me play. I regularly play in Miami for the Winter Music Conference and Art Basel, that’s my two gigs a year mainly there. Towns like San Diego and San Francisco have a scene, too. Most of the places have a scene as such. It’s not the biggest scene, but with all the internet communication and stuff like that it’s small but healthy.

And since you are allowed to travel again, is it some kind of relief and you accept many gigs abroad?

Not really. It is nice to travel and just to have the freedom. I haven’t been around for ten years so it’s nice to pop out and go to Japan and Europe again. But I don’t plan to spend the next ten years on the road. There are a lot of opportunities, basically everywhere I ever played before plus twice as many places again.

How does it feel to get out again? Has the scene changed in the meantime?

I don’t think it has changed at all.

Is that disappointing?

No, that’s not disappointing at all. I always had a good time. There are certain focuses on particular kinds of music over the years, whether it’s Electroclash, or Minimal, or Drum ‘n’ Bass, but in general the dance music scene still goes bang bang bang between 110 and 130 bpm. And I don’t really see boundaries between the so-called genres. I play the music that I like, whether it’s a Techno record, or a Disco record, or whatever. I think more than the music has changed the people have changed. Kids that weren’t born when I was DJing in the mid 80’s are now in their mid 20’s, there’s a whole new generation of people who have come through as well as the survivors from the old school. The formula of a dance party is still very similar. I suppose communication via internet had an impact. Even though I have been away for ten years people know exactly what I have been doing. It’s not like I completely disappeared during that time. The networking has made sure that my influence via production or gossip has been maintained.

I think the internet helped to keep your status alive. All you did was thoroughly discussed on specialist websites and message boards. I guess this is quite different to how it was before.

Yeah. Scenes used to be localized, and now it’s globalized. Which is good and bad. If something fresh happens in a small area it doesn’t have time to develop, it is instantly global. Early Punk or Hip Hop had two to five years a hardcore scene as such. Whereas now, as soon as there’s a bright idea it’s everywhere in the world and everyone’s had a piece of it before it maybe manages to have a big foundation.

Nowadays it might also be easier to get influenced by another DJ, or even to imitate somebody. In pre-internet days you could maybe get your hands on some mixtape, but it was difficult. Maybe you read about DJs, but you never had the chance to hear them. And now you can download tons of sets from legendary DJs, and from legendary clubs, too.

Yeah. I think that’s good and bad, too. These days I don’t let people record my sets. I suffered from heavy bootlegging. And a lot of the time when I play it’s for that moment. Maybe you’re sitting in your car, listening to a set, but you have no idea of the atmosphere or the climate at the moment when the record was being played. The tape might sound bizarre or disjointed or strange and it might not particularly work in the car or the boutique or at home. But at the particular moment, that was the right thing to do. So I try and keep my sets for the people who were there and it’s for memory banks only.

So you think it gets watered down?

It’s a double-edged sword. Sometimes there’s a little bit too much access. Some of the mystery is gone. If you think of DJs like Ron Hardy, I’ve only see one small grainy photograph of him, and you wonder who this guy is and what his character is. If you want to find about me, just hit Wikipedia, DJ Harvey images, and you know what I look like, my style. But there is a little mystery to who or what I am and I quite enjoy that. Luckily the personal appearance still counts for something. Because they have had absolutely everything besides me physically. And here I am, in the flesh, I actually exist. I’m not just this digital entity. Read the rest of this entry »

Posted: November 6th, 2006 | Author: Finn | Filed under: Artikel | Tags: Boris Dlugosch, Front, Groove, Klaus Stockhausen, Phillip Clarke, Willi Prange | 9 Comments »

„I can’t even dance straight.” (Aufdruck eines Front-Tshirts)

Das gängige Club-Koordinatensystem in Hamburg Mitte der 80er bewegte sich irgendwo zwischen Mod-Kultur und Northern Soul sowie Post-Punk und Wave in Läden wie dem Kir und Disco-Poppertum im Trinity, Voilà oder Stairways. Welcher Hafen angelaufen wurde, entschied sich meistens danach, ob der Schwerpunkt der Planung auf Musik bzw. Tanzen, Mädchen oder Saufen gelegt werden sollte. Diese Komponenten kamen zwar manchmal auch an einem Ort befriedigend zusammen, aber in der Hansestadt wurde schon immer bei ersten Anzeichen von diesbezüglichen Ungleichgewichten der Standort verlagert. DJs mixten in der Regel nicht und die Musik war oft ziemlich durcheinander und demnach war man es auch gewohnt, nur hier und da zu tanzen und den Rest der Nacht anderweitig auszufüllen.

Etwas ab vom Schuss, Nähe Berliner Tor, gab es dann noch das Front, das Willi Prange 1983 eröffnet hatte. Der Stamm-DJ dort war ab 1984 der Kölner Klaus Stockhausen, der ebenso wie andere DJs in der Stadt eine Mischung aus Boogie, Synthpop, Electro, Hi-Energy und Italo auflegte. Dennoch hatte das Front im Rest der Stadt schnell diesen speziellen Status. Das lag einerseits sicherlich daran, dass das Publikum dem Vernehmen nach fast ausschließlich schwul war und sich nicht groß darum kümmerte, sich jedes Wochenende so abseits von Kiez oder Alster zusammenzufinden. Andererseits lag das aber auch vor allem an Stockhausen, der seinen Kollegen in vielerlei Hinsicht weit voraus war.

Von seinen besonderen Fertigkeiten als DJ erfuhr zuerst ich von einem meiner besten Freunde, der ein klein wenig älter war und schon ab 84 regelmäßig hinfuhr. Dort kaufte er Stockhausen irgendwann einen Schwung Live-Mitschnitte auf Kassette ab, für ganz schön gutes Geld, der Mann wusste eben was er wert war. Als ich die Tapes zum ersten Mal hörte, war ich ziemlich baff. Ich hatte ein langjähriges Faible für alle Arten von tanzbarer Musik, aber was man damit im Mix anstellen konnte war mir eher fremd. Ich erkannte Teile meiner Plattensammlung wieder, aber irgendwie klangen die anders, energetischer und aufregender. Es liefen viele instrumentale Versionen, versetzt mit Soundeffekten, Scratches und Acapellas. Verschiedene Platten liefen minutenlang zusammen, oder Teile davon nur wenige Sekunden. Die meiste Zeit konnte ich die Stücke gar nicht auseinanderhalten. Ich hatte keinen Schimmer, wie man so was hinbekommt. Die Musik-Auswahl war dabei durchweg geschmackssicher und abenteuerlustig zugleich. Live muss das der Hammer sein, dachte ich.

Tatsächlich waren die Nächte im Front zu dieser Zeit schon ziemlich ausgelassen, doch richtig Fahrt kam ab Ende 85 auf, als bei Tractor und später Rocco und Container Records die ersten House-Importe eintrafen. Ich bekam House erst mit, als „Jack Your Body“ und „Love Can’t Turn Around“ 1986 plötzlich Hits wurden, aber es gefiel mir auf Anhieb. Es erschien wie die perfekte Synthese von allen möglichen Club-Stilen, war aber gleichzeitig total primitiv und direkt. Eine verheißungsvolle Variante in der Chronologie von Disco sozusagen. Im Front wurde House nach Ohrenzeugen vom Fleck weg vereinnahmt, es gab zwar nicht viele Platten zu kaufen, aber was verfügbar war, wurde auch gespielt. Die europäische Clublandschaft ist sicherlich zu diffus und weitläufig, um wirklich exakt die historischen Initialzündungen zu benennen, aber wenn man sich mit der entsprechenden Geschichtsschreibung in anderen Ländern befasst, war Hamburg verdammt früh dran, ohne davon viel Aufhebens zu machen. Die regelmäßigen Wochenendgäste aus England schienen sich jedenfalls mit voller Absicht zum Tanzen in die touristisch unterentwickelte Gegend am Heidenkampsweg zu verirren.

Das erste Mal dass ich tatsächlich ein Teil der schrägen Schlange wurde, die sich zeitig vor den Stiegen abwärts sammelte, war Anfang 87. Ich war fast volljährig und etwas angespannt. Die coolen Typen um mich herum schienen es kaum abwarten zu können, von dem mürrischen Kerl mit dem Schnauzbart durchgewunken zu werden, der die Tür zu dem Keller verwaltete. Das Publikum bestand zur stolzen Mehrheit aus schönen Jungs in glammigen Outfits und halbnackt-muskulösen Lederkerls, und es war zahlreich erschienen und schrie sich auf der Tanzfläche bereits geschlossen die Seele aus dem Leib. Der Club an sich war absolut unglamourös. Karg war noch untertrieben. Die Wände waren nackt bis auf ein paar Notausgangschilder, auf denen ab und zu „Danger“ aufblinkte und gelegentliche Diaprojektionen mit Worthülsen wie „I mean…is he…“ oder „…and suddenly…“. Die Tanzfläche war gesäumt von niedrigen Podesten mit Geländer, die einen bei der niedrigen Decke noch näher an die fiesen Horn-Hochtöner brachten, Bestandteile einer Anlage, die nicht unbedingt gut war, aber sehr effektiv und vor allem sehr laut.

Die Lightshow bestand lediglich aus verschiedenfarbigen Neonröhren, die sich über der ganzen Tanzfläche erstreckten und in unnachvollziehbaren Intervallen ins Dunkel blitzten. Und im Gegensatz zu anderen Hamburger Clubs war es sehr dunkel, gepaart mit einem ungemein stickigen Dunst von mehr oder weniger nackten Körpern und Poppers, der stetig von der Decke tropfte und als dichter Nebelschwall über die Belüftung direkt neben den Eingang wieder auf die Straße zurückgeleitet wurde, als sollte er wie der Rauch bei der Papstfindung der Außenwelt künden, was für eine Stufe des Exzesses dieses Wochenende gemeinsam erreicht wurde.

Man kam eher zum Tanzen als zum Posen ins Front, auch wenn man bei Bedarf beides gleichzeitig konnte, und ließ sich von der wummernden Pracht von links nach rechts schicken. Die Stimmung war physisch und bis zum Anschlag sexuell aufgeladen. Die Front Kids hatten ihren Tempel eingerichtet und huldigten dem Hedonismus mit bedingungsloser Loyalität. Alles war egal, solange es Spaß machte. Wenn man sich überhaupt von der Tanzfläche entfernen wollte, waren die einzigen Ablenkungen eine Theke mit ein paar Bänken ein Gewölbe tiefer, deren Zapfanlage unter Gejohle von mitfeiernden Barleuten zum Beat bearbeitet wurden, die nicht selten im Torerokostüm den Dienst antraten, ferner notorische Toiletten mit äußerst regem Verkehr und deaktivierter Geschlechtertrennung sowie ein Flipper, der nie funktionierte.

Der ganze Überschwang hatte souveräne Methode, die von einem DJ-Bereich gesteuert wurde, der sich in einem wesentlichen Punkt von anderen unterschied; man konnte den DJ nicht sehen. Die Kanzel war eine erhöhte dunkle Box, die von der Tanzfläche aus durch eine Tür zugänglich war, der DJ schaute durch zwei winzige Schießscharten heraus und war selbst nur schemenhaft zu erkennen. Das hatte durchaus den Effekt, dass man sich auf die Musik konzentrierte bzw. dass die Musik teilweise wie aus einer anderen Welt herübergesendet kam, obwohl man sich natürlich sehr wohl bewusst war, dass der zuständige Zeremonienmeister etwas Besonderes war, was denn auch mit viel Geschrei auf dem Floor honoriert wurde.

Eine konsequente Absage an die fortschreitende Personifizierung des DJs, aufgrund derer Stockhausen schließlich 91 für immer die Kopfhörer für eine ebenso erfolgreiche Karriere als Moderedakteur bekannter Lifestylemagazine niederlegte. Wie er aussah wusste ich erst Jahre später dank einer Fotostrecke in einem Stadtmagazin, es war auch nicht wichtig. Gleiches galt auch für seinen überaus talentierten Nachfolger Boris Dlugosch, der ab 1986 Stockhausens Protegé war und nach dessen Rückzug den Taktstock übernahm und ebenso stilprägend die nächste Ära des Clubs dirigierte und weitere DJs wie Michael Braune, Michi Lange, Sören Schnakenberg und Merve Japes. Promis wurden vermehrt gesichtet, aber kaum beachtet. Diese Rahmenbedingungen sollten sich für die nächsten Jahre nur unwesentlich ändern. Es gab Rituale wie den Laster von einer Quadrophonie-Testplatte, der bei gelöschtem Licht durch den Raum knatterte und meistens die Schlussphase mit einem Rückblick auf Disco-Klassiker einläutete, die allerdings auf dem Front-Soundsystem klangen, als wären sie in einem Kugelblitz wiedergeboren worden. Es gab diverse zügellose und Spezialveranstaltungen mit wechselndem Motto und den jährlichen Geburtstagsrausch, bei dem immer noch eine Schippe draufgelegt wurde. Unvergessen dabei der Auftritt eines unbescholtenen Straßenmusikers, der anlässlich des ersten Golfkriegsausbruchs von der Einkaufsmeile wegengagiert wurde und dann nervös vor dem ekstatischen Auditorium „Give Peace A Chance“ klampfte.

Bei der Entwicklung von House und allen daraus resultierenden Stilarten war das Front in den folgenden Jahren eine unerbittliche Messlatte. Zuerst kam die Acid-Phase, die auch über andere Neueröffnungen wie das Opera House, Shag oder das Shangri-La die ganze Stadt eroberte, und Detroit Techno wurde in der ersten Welle herzlich umarmt. Ausflüge in Clubs anderer Städte zu dieser Zeit vermochten im Vergleich nicht so recht zu überzeugen, man freute sich bereits auf das nächste Heimspiel. Ab 89 kamen die New Yorker Hybriden aus Techno und House der Marke Nu Groove und Strictly Rhythm dazu, und man verneigte sich gelegentlich vor den Post-Acid-Entwicklungen der Insel, Bleeps etwa, oder Shut Up And Dance und 4 Hero, damals noch Breakbeat Techno genannt.

Als Techno sich ab 91 mehr und mehr über Härte definierte, besann man sich im Front jedoch auf die hauseigene Tradition des Groove und überließ das Geheize Läden wie dem ersten Unit. Die Anteile von Garage und Deep House wurden unter der Ägide von Dlugosch quasi über Nacht nach vorne gemischt, ohne dass die unbeschwerte Dynamik auf dem Floor Einbußen erlitt, der Rausch klang nur etwas anders. Das Front verband Schub mit Stil und hatte seine Jünger bestens mit House erzogen und so wurde aus Hamburg, im Vergleich zu anderen Metropolen, nie eine Technostadt.

Der Club wurde in der Face, im I-D und in der Tempo als Weltklasse bestaunt und war auch mit Dlugosch mindestens auf Augenhöhe mit Clubs der reinen Lehre in den USA oder England und in Kontinentaleuropa lange Jahre praktisch konkurrenzlos, was nicht zuletzt dadurch untermauert wurde, dass das Front auch sehr früh begann, die Heldengestalten aus Übersee zu buchen. DJ Pierre versagte Wild Pitch und machte das mit Acid trifft Garage wieder wett, Mike Hitman Wilson versagte einfach völlig, Frankie Knuckles legte ein Handtuch um und eine Flasche Cognac und Tischventilator vor sich und breitete das große Gefühl aus, die Murk Boys waren gegenseitige Liebe auf den ersten Blick und Derrick May wollte gar nicht mehr aufhören.

Diese ersten Gäste vermittelten aber auch Einblicke in andere Szenen, was immer mehr Clubgänger interessierte und die Konkurrenz in der eigenen Stadt nahm zu und bediente sich beim Standard des Front. Die schwule Basis fühlte sich mehr und mehr von Neugierigen bedrängt und die Faces der ersten Generation zogen sich langsam zurück, der Geist der Pionierzeit verlor auch in der Musik an Strahlkraft und selbst die Nachttanke um die Ecke war plötzlich nicht mehr da.

Dennoch empfand ich es wie viele als Privileg, speziell an diesem Ort live zu hören wie sich das Haus erbaute, in dem wir heute noch allesamt wohnen. Nur lief die Chose irgendwann von ganz allein und an anderen Orten und ich ging ab 94 immer sporadischer hin, bis mich dann 97 die Nachricht von der Abschiedsparty wachrüttelte. Ich zog es vor, es in Erinnerung zu behalten wie es zu besten Zeiten war und bin nicht hingegangen. Das Inventar wurde später, einer echten Clublegende angemessen, wie Reliquien meistbietend versteigert.

Das perfekte Souvenir hatte ich aber ohnehin schon, es ziert noch immer meine Zimmertür: das Schild von der Damentoilette, mysteriöserweise eines Sonntagmittags auf meinem T-Shirt klebend, als ich in voller Montur auf dem Fußboden eines Kumpels aufwachte. Gute Zeiten. Klaus Stockhausen ist immer noch der beste DJ, den ich jemals gehört habe und die Intensität des Clubs bleibt für mich selbst minus sentimentaler Verklärung unübertroffen. Es hat mich tief geprägt. Wenn ich von Berlin nach Hamburg hineinfahre werfe ich jedes Mal einen verstohlenen Blick auf das Leder-Schüler-Gebäude und habe Musik im Kopf. This used to be my playground.

Mit besonderem Dank an Walter Fasshauer, Patrick Lazhar und Frank Ilgener.

Groove 11/06

Danke für alles, Willi Prange und Phillip Clarke… R.I.P.

Recent Comments