Interview: David Morales

Posted: August 15th, 2016 | Author: Finn | Filed under: Features | Tags: David Morales, Groove, Interview | 6 Comments »We should probably start at the very beginning. What were your baby steps as a DJ, what led you to being a DJ in the first place?

I think in the first place was the love for music. And I can remember when I was really, really young, with a babysitter, and we’re talking about the days of 45s. The first record that I actually remember and I was spinning was „Spinning Wheel“ by Blood, Sweat & Tears.

Good choice.

You know my family was from Puerto Rico and there was no American music in my house.

It was mostly Latin music?

Only Latin music. And we’re talking about Merengue, Salsa. Folk music from Puerto Rico. And I didn’t like it. And it’s funny because today I appreciate Latin music. Since I became a producer, now I appreciate Latin music for the production, the instrumentation, the musicians, because Latin music is not machine-made, not at all. So the first 45 that was in my house was “Jungle Fever” by Chakachas. My parents had this fucking 45 that was this erotic fucking record. And we’re talking about these stereos that were like these big fucking wooden consoles with the big tuner for the radio and the thing with the record where you put some records in the thing and it dropped one at a time and when it ended the thing drops. It must’ve been when I was about six or seven there was an illegal social club. You know I was living in the ghetto. So there were illegal social clubs that were like a black room, with day-glo spray paint, fluorescent lights to make the paint glow and they had a jukebox. And they’d play the music back then. „Mr. Big Stuff, who do you think you are“. It was all about the O’Jays and that kind of music. And I liked that. I used to sneak downstairs and such.

So when was that?

It was like the late sixties. Because I was born in ’62 so by ’70 that makes I was 8 years old. So it was before that because then I moved. Anyway, so fast forward the first 45 that I liked was the O’Jays. The first 45 I actually bought. And I remember playing that record I a hundred times a day. Putting the bullshit speaker we had in the house outside the window, we lived on the first floor. I played the record to death.

So you played it to the whole neighborhood?

The whole neighborhood. The only record I had really. So then when I graduated elementary school, I used to be into dancing, like the Jackson 5 they had “Dancing Machine”, there were The Temptations and Gladys Knight & The Pips and I liked that music. So then when we got into Junior High School – when I was like 13 years old, I had a girlfriend and we went out when the first DJs came on in the neighborhood, which was like the black DJs. I saw the first two Technics set up and a mixer in someone’s house. I was like “Wow! That’s interesting.” I saw somebody doing this non-stop disco mix and I never knew what that was all about. So, I used to hang out with all my friends. I was a dancer, we used to do all this what we now call breakdancing. We would do battles. So, I had one turntable and my friend would say “David, we hangin’ at my place” and I would play some music for us. So I just was a kid that sat by the stereo with the records and put on the tunes, one at a time. Because back then that’s what it was, you’d play one tune at a time. If it ended, the people clapped and you’d play the next tune. And it was all songs.

How did you proceed from there?

I was one of those kids that used to go to the record store even though I had no money. Just to look at the records. To walk by a store that sold turntables and a mixer and be like “one day, one day…” And I’m not working so I can’t afford to buy anything. My first mixer was a Mic mixer. 1977 there was a blackout in New York and there was a lot of stealing so I came across a radio shack little Mic mixer that I set up to make it work with two turntables. You had to turn two knobs at the same time and it was like mixing braille because there was no cueing. My one turntable had pitch control, the other one had none. I was too young to go to clubs, so I never saw a proper DJ mixing. I only saw people outside, we would have block parties and people would be mixing. And I was one of those kids that was just standing there, watching. The first time I went to a club I was 15 years old, it was Starship Discovery One. It was on 42nd street in Times Square, and we got in. We shouldn’t have got in, but you know it was the end of the club, I was 15 and I got in. The DJ had three Technics, the original 1200s, and a Bozak mixer. The booth was a bubble, and I had my nose at the fucking bubble and I was just mesmerized. The first time I actually played on a real mixer I went to a house party at my friend’s brothers apartment. And in those days, most of the DJs who were really playing were gay DJs. “San Francisco” by the Village People was the big record. But I was into The Trammps, I was into James Brown, I was into Eddie Kendricks, Jimmy Castor Bunch, “The Mexican”, Sam Records and of course Donna Summer and all this kind of stuff. So I went to this house party and he was the DJ, the first proper mixer I saw – this was before I went to that club. And it was a black mixer, it had two faders and it had cueing. So I see the DJ there, he’s using headphones to cue. So my friend says “D, you wanna play some music?” and I’m like “Yeah, sure.” I grabbed the headphones, put them on and I hit the cueing, because I was watching the guy, and I’m hearing some music and and I was like “Oh shit…” When I played at that party, I’d still play how I know how to play, which was braille. Intro, outro. And it wasn’t about mixing. All the new bars at that time were advertising nonstop disco mixes.

It was even mentioned on the record sleeves.

Yes. And all that meant was that the music never stopped. Because before the music used to stop before the next record came in. So now it was continuous. That worked, so here came the name nonstop disco mix. And then at that time all these records started coming out. The disco 45 record. At my junior high school prom “Doctor Love” by First Choice was big. And I remember the guy playing it about four times. So my first 12″ of course was “Ten Percent” by Double Exposure, on Salsoul. Another record that I played to death out the window.

You were still doing that?

I was still doing that. I used to live to just play music. I loved it. I would leave in the morning to go to school because my parents would go to work. I would buy a bag of weed, buy a quart of beer and I would go home. And you know in the old days we had all those buildings where you could really play loud music and I had these stupid double 18 boxes in my fucking bedroom. Before I’d take a piss, I turned my system up. My mother used to be like “turn that music down, turn that music down, turn that music down!”

Did you begin to play out around that time?

Yes, and playing at parties in those days meant you carried your records. Because you didn’t play for two hours, you played the whole party. And the thing is, if you owned 5000 records, you took 5000 records to the party. And in those days we carried milk crates. So here I am carrying eight to ten milk crates to a party. Getting in a car, getting a cab, you have all your friends who would help you going there, but when you’re leaving there is nobody to help. And you had to take the stereo system with you. So you carry the sound system and you carried your records. You took everything. It wasn’t like going somewhere and you just bring your records and they have everything. You had to take everything. I did parties for 15 dollars, for 25 dollars and you had to chase people down for your money.

What kind of events were you doing?

I played in clubs, I did Sweet Sixteens, I did weddings, I did corporate events. I did anything. I also did parties in high school. I would advertise a party, we would bring the sound system to some kid’s house, the parents left to go to work, we’d bring the sound system fast, and I would advertise free beer and free joints. Even 50 people is a lot of people in somebody’s apartment. Imagine we’d take over the apartment and it’s like 10 in the morning and we’d be fucking banging it, banging it, banging it — and we’d get out by 3 in the afternoon before the person’s parents come home. God knows the mess, whatever the case, baby. And in those days the sound system was in the living room, the DJ booth in the bedroom. No monitors, it was just bang bang bang. As I started doing parties at an apartment I used to charge a dollar to get in, decorate the apartment, put up balloons, and it just started with friends. Obviously still free beers, free joints, the whole thing. And like I said, I just loved the music, it was just everything for me. I wanted to play every single day. Even when I didn’t have the equipment, I knew friends that bought decks and a mixer and a small sound system for their house and they weren’t DJs and they used to say “David, come to my house and play music for me.” And I would just die to play, it was just everything for me.

How did you begin to promote your own events?

I played at a party for someone at a club in Brooklyn and the only people that showed up were my friends, so I approached the club and said “Can I do a party?”, and what started as once every couple of months became once a month and then became every Friday. I used to design my own flyers, after work I used to decorate the club. I used to do everything, I used to put up balloons, put out fruit, and it was an afterhours. And I worked with other promoters or hosts. The little bit of money I was asking for was a 100 or a 150 dollars. I was pulling teeth with people. I rented the club, I was running the whole logistics, the door and everything. So, as these parties went on, when I did a couple of parties with different hosts, what I realized was that everybody was coming for my music. It had nothing to do with the host. So that’s when I started to do my own parties.

How had the music changed you were playing then?

At that time the only thing I knew was commercial music, so the music I bought was the music you heard on the radio. I bought it at a record store. And I played once for somebody’s party, it was a surprise party for someone and there were some older people that used to go to a club called The Loft that was owned by David Mancuso. And I think I was about 18 years old. And somebody bought me like a stack of records of what they called Loft records and it was records they weren’t only playing at The Loft, they were playing them at the Paradise Garage, but I never went to any because they were both membership clubs. So when I first heard these different records, I was like “Whoa, what is this sound?” They were a lot of imports, none of those records you heard on the radio. So of course I wanted to know where to buy these records. I used to go to commercial record stores. There was Rock and Soul, there was Downtown records, and Vinyl Mania had these Garage and Loft classics. And some of them were very expensive, 25 to 50 dollars or more and at that time a 12″ was two or three dollars. So for me these old collector records and imports were really expensive.

So the clubs you were going to changed as well?

Every single weekend. I used to go to the Loft on Saturdays, before I did those parties. I was a dancer. I used to take LSD, god, and I was one of those party kids that would go to the Loft, go to the Paradise Garage and come home and play records – because I was inspired, and still fucked up. So I was doing these parties on a Friday and I would go to The Loft on Saturday. And David Mancuso gave me some books. I learned about sound and then then I got my first Urei and it was a big thing. And then in 1983 I joined Judy Weinstein’s record pool which was called “For The Record.” A record pool was a place where people paid a monthly fee, 50 dollars a month. It was a place where all the record companies would send their promos to. It could be a month before the official release date, two months, three months, it could be four months.

So it was essential if you wanted to have a DJ name in New York to be a member?

Well, to be a member at the record pool you had to be employed at a club. You couldn’t just join it. No, you had to prove that you played at a club.

And you were recommended?

A friend of mine, Kenny Carpenter, was a member of the record pool and he brought me there. Of course I was playing, but you had to get a corporate seal from the club, they had to be able to check that you were really playing at the club. And Larry Levan was a member of the pool, François Kevorkian, Jellybean, Tee Scott and all the big name DJs in the Tri-State area. It was 125 members. Also all the top remixers at that time, like Bruce Forest, Steve Thompson. And I used to give Judy Weinstein cassettes of my sets.

Were you already mixing at that time?

In 1980? No. I wasn’t even editing, I wasn’t doing anything yet. She recommended me to play at the Paradise Garage. I had never played in New York City. Never. I had been to the Garage, it was like the Mecca. Everybody knew Larry Levan. “He plays on four turntables”, all this kind of stuff. I used to go there, mesmerized, but I’d never been to the DJ booth. Fridays was straight, Saturday was gay and I went to the straight nights. I was with my friend Kenny Carpenter at my house, and he had played at Studio 54, he had played at Bonds International. He deserved to play at the Garage. There were many other DJs like Tony Humphries that deserved to play at the Paradise Garage before me. But Larry would have such a big personality, people were so scared of him because Larry Levan was Larry Levan. Even though he didn’t own the club but the Garage was Larry’s club.

So he preferred DJs that had not that big a name?

They wanted somebody that wasn’t part of the politics. In a sense. So I’m in my house with my friend Kenny and I got a call from the owner and everybody knows the name of the owner and he says “Hello, my name is Michael Brody, I own a club called Paradise Garage” and I’m like “Yeah boy, who the fuck is fucking me.” He says “Our DJ has been playing like shit and I would like you to come play in my club.” And I fell to my knees. He never heard me play. I never played in New York City, I played in Brooklyn, at a place in my neighborhood, with about a hundred people.

That’s quite a leap forward.

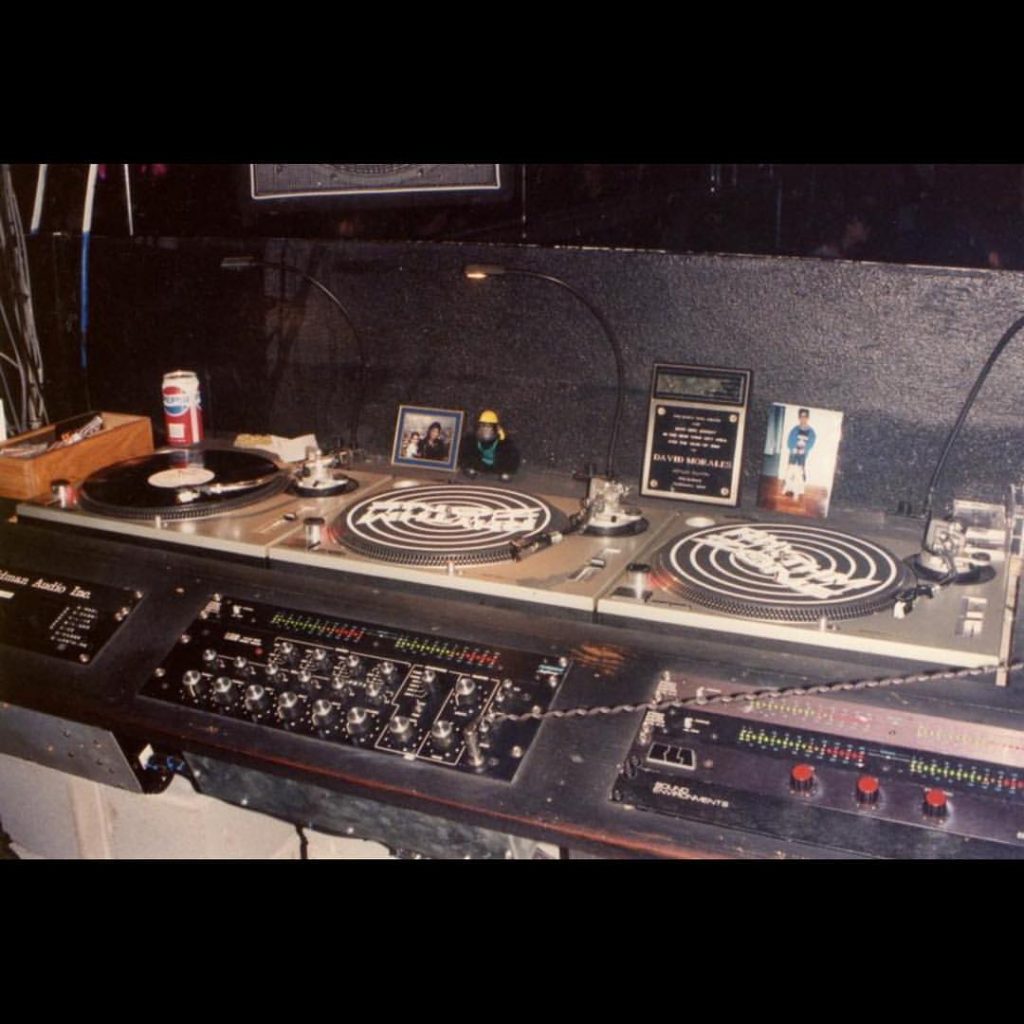

The number one club in the world at that time was the Paradise Garage. A big sound system. Grace Jones? Mick Jagger? Everybody went to the Garage. I’d never been to the booth, I used to go there as a dancer! So, he offered me two nights and I knew the Garage was straight on Friday, gay on Saturday and he goes “I want to give you two nights, you can play two Fridays or I would like you to do Friday and Saturday.” And I said, “Listen, I don’t think I can handle the Saturday because I’ve never played for a gay crowd before.” He said “I just want you to come here and play music.” That was it. Okay, so I go to the guy in the booth and I was used to playing on 1200s. They have Thorens 125 Mark IIs, belt-driven. That’s a whole another science. The console, two reel-to-reels, it was like the Starship Enterprise. I was like “Can you put in Technics?” And they were like “No, you have to play on our turntables.” And I was like “Shit.” So they put my name on the marquee and they advertise my club, Ozone Layer. And people were like “Whose dick did you suck to play at this club, how did you get to play here out of everybody?” Because maybe only two to three other DJs besides Larry ever played there. And they were part of the cycle. It was just Larry Patterson and Tee Scott. François Kevorkian played there too, and he used to do the visuals and play drums there. So I play, Friday and Saturday, and they said I could bring whatever acts I wanted, whatever records I liked at the time, and one was Jocelyn Brown and I played Friday and Saturday back to back, 11 hours each night. And the turntables were amazing! And every DJ had their groupies. When you were resident at that time, you had all your groupies. And Larry was Larry. So if people hated me and they would thrown darts and knives and arrows behind my back, I didn’t even know, I didn’t even care because I didn’t know anybody. So that weekend put me on the map. My level went from here to there, from one weekend. After that I played ten times there. After that I got asked to play at this club called Inferno where they started with ten DJs, like a battle, every weekend, and they would finalize it to one guy. And of course, I ended up the one that they hired. And I remember I played first, and after I played that guy was supposed to play and said “No, you got it man, I can’t fuck with you man.” I started working for Judy at the record pool in 1984. I bought a reel-to-reel and I was editing my little mash-ups. And then I met a remixer, his name was Bruce Forest.

Who used to play at Better Days. Did he help you with your first steps in the studio?

Yeah. First he took me to the studio. I was intrigued, so I bought my first sampler and things. He was an incredible DJ and he inspired me. In 1985 I had a drum machine and a keyboard in my DJ booth. In 1985 he had a keyboard, a drum machine, he had two Korg samplers with a homemade trigger sampler using a keyboard pedal and even though I couldn’t play a fucking note I started to try and started editing for producers. Because in those days there were half-inches, there was no automation. So they would give me ten boxes of reels of different out-takes and from there I had to edit together a 12″ and a radio mix. So I had to listen to it. Each box had 15 minutes. So 10 times 15, you get a 150 minutes of music, that you had to make into a version. So the radio can’t be more than 4 minutes and a 12″ in those days maybe was 8 to 9 minutes. So I started with that and then I did my first remix, it was 1986. I’m a big fan of Imagination. And in 1987 from the UK Stock Aitken Waterman went big, because they had Rick Astley, who was big at that time. So, here I got this remix because I worked in the record pool, this remix of Imagination, it was called „Instinctual“ and it was mixed by them and it sounded like a Rick Astley record. So I told the promoter „This is not Imagination! This sounds like a Rick Astley record!“

They deserved better?

Yes! And I asked “Can I do a mix?”, and he said “Well, we have a budget of 5000 and I have to allocate it”, and I’m like “Please give me a chance.” It was a Arthur Baker production. I had Josh Milan from Blaze, who was 18 years old at the time, that did keyboards for me. So I did a record, it was out of key, and Arthur Baker and the group were like “But you really don’t understand anything.” “But it sounds great, you know.” And they were like “But it’s out of key!” Anyway, to make a long story short: It was a big record. Huge. Even Larry Levan said it was a great remix and I was like “Wow, oh my god, Larry Levan” So that was my first official remix. Then up there, I got asked by Jellybean to mix Whitney Houston’s “Love Will Save The Day”. Whitney Houston was brand new at that time. So, I did the mix and they said it was too black, too underground. So the day of the release I was heartbroken, because that mix was so important for my career and who was big at that time? Taylor Dayne, mixed by Ric Wake. So he mixed it, and he did this Taylor Dayne styled four to the floor House mix. I remember the promotional guy because I used to work at the record pool and knew the promotional guys, and he said „What do you think about the new Whitney House mix?“ That was no House music! I was playing House at Zanzibar with Tony Humphries. House music was new, it wasn’t even really there yet. So there was this promo guy, what do you know about House music? But in the end they released 250 limited promo copies, it was one of the most hard to get records, because you couldn’t get it at a store. Only if you were in a record pool and there were just limited copies. Years later DMC ended up releasing it. And then everything just started moving and in 1989 I took a trip to the UK.

That was the beginning of your international career?

I was just starting to do remixes and it was the first time that I played in the UK, during the DMC chanpionships. I was asked by Nicky Holloway and Pete Tong to be a guest DJ, they were playing and doing the Sin parties at the Astoria. I go there with my records, thinking I’m going to do a proper set. I warmed up for 55 minutes and then Pete Tong comes to me and goes „Thank you mate, that was great“, and I’m like „Listen, I don’t care about the money“, and he goes „This is how we do things here“ and I’m like „Uh-huh“ and all the people from New York that came there were like „What happened?“ and I was like „They told me that, 55 minutes, yeah they told me that that was it.“ Anyway, I was doing more remixes for the UK than America. All my remixes were coming via import. And I was playing at the Red Zone, 1989, and the Red Zone was like Studio 54 of that time. Everybody used to go there, it was all about being upfront. The new club kids. I came back from the UK with Soul II Soul „Keep On Movin“, that was major at the time. There was some of the great stuff, Snap’s „The Power“. I was the first one in New York to play „Pump Up The Jam!” We ended up remixing it for SBK Records, because it was just massive.

But were the other DJs in New York not touching it because it was European?

They didn’t go to the UK. They weren’t buying those records. I would come to the UK and buy records.

And you broke them in New York?

Yeah. Every other club was playing New York house or American house, nobody was touching the European stuff. You couldn’t get away with it. But because Red Zone was the chic place, or the most happening, it was acceptable. I was playing KLF’s „What Time Is Love“ and people were like „Yo, what the fuck is this record?!“, „What is this, what is this?“. I did „Dirty Cash“ by Stevie V, I had the import and in the UK they were never into artist development. They you used to put out a lot of records and just throw them up, throw them up. Some stuck, but they were just ready to go on and then move on to the next thing. „Dirty Cash“ was a big record for me at the Red Zone, and I went back to them and said „Let me remix the record“, and after remixing it an American label picked it up. And then also for the UK it became the number 2 pop record. So, the Red Zone for me was really like a combination of American and UK house.

What made the club so special that you kind of started developing that signature Red Zone mixes which were more like a darker style?

The dubs were the Red Zone mixes. The dub was really like a break of the 12“. So the break really was what became the dub. Mostly no vocals or some vocals, it was just the dark side. And the Red Zone was the only place that you were hearing that kind of music. And that’s how the Red Zone mixes became famous. Then afterwards I started mixing records for the American companies. I was also playing Reggae. Well, it wasn’t called Reggae, it was called Dancehall. And some Hip Hop. I was playing all of that stuff.

You did some mixes back then for Shabba Ranks or Carleen Davis.

And Shabba Ranks was a huge record. I mean, it sold millions! Anchor Records picked it up and said „Give me something that you would play.“ I changed the whole thing, I sampled Maxi Priest, they changed the name of the record. The original name of the record was „Champion Lover“. And because I made it „Mr. Loverman“, they changed it and made it „Mr. Loverman“. And of course Ce Ce Peniston was big record for me at that time. „I’ll Be Your Friend“ was a big Red Zone record, that was 1991.

How long was your stint playing at the Red Zone?

Three years.

But those were crucial years, right?

Yeah. You had the Red Zone and the only afterhours was the Sound Factory. Ok, you had Save The Robots and some small kind of cool things, but it was the Sound Factory. So people would go to the Red Zone because it was the early part and then from there they’d go to the Sound Factory, because it would be open until the afternoon. When I was playing, besides having records, I had levels of reel-to-reels because all that stuff wouldn’t be coming out until two or three months later. So Ce Ce Peniston’s „Finally“ or „Gypsy Woman“ by Crystal Waters, I was playing that shit three months before it even came out. But I was playing it all from reels. The record companies would come to people like me, Larry Levan and Junior Vasquez and Frankie Knuckles with reels hot of the press from the studio to break them. I remember when I first got „Gypsy Woman“. People were like „Wow, what is this record?“ And in those days, because it was not on the radio, it was not in the stores, that was the only time they heard those records. That’s how Larry had the power, Tony Humphries, Bruce Forest, because we’d play stuff that wasn’t available and people would come to the club and wait to hear those records that you couldn’t get. They waited and then „Whoa! There it goes! boom, boom, boom!“. So I started Fridays and Saturdays, I was a resident and then I stayed on. I was in the studio five days a week, a 100 hours. I used to sleep in the studio. It was my home.

When was the time you founded Def Mix?

It was 1987. Frankie Knuckles moved back from Chicago and he started playing at a club called The World. The World was before Red Zone.

But you knew him before?

No. I just knew of Frankie. But that’s when we started. Because he was starting to get mixes and the reason I came up with the name Def Mix was because at that time the slang in Hip Hop was Def, like Def Jam and so on. And Def was good. So because Shep Pettibone used to have „remixed by Shep Pettibone for Mastermix Productions“ we’d go „remixed by David Morales for Def Mix Productions“. So that’s how we started. We never intended it to be something.

Why did you decide to put it together, as a company? Just to organize it, all the requests?

No, because Judy was managing both me and Frankie but me and Judy just decided to create the company. Because there were so many requests coming for me and Frankie and we were like the Gamble & Huff at that time. We had a stable of musicians, I used to do all of the drum programming for Frankie’s. We used the same musicians, the same engineers, we worked at the same studio. That’s why we had the so-called Def Mix sound.

The discography of Def Mix Productions is just incredible. So, so many remixes. And you had the discography on your old website where there were quite a lot of unreleased remixes even. There probably was no remix team with such a high output for years.

Well, the other one was Masters At Work. But they came a little behind us, so we were the first ones in 87. And from everybody, Pet Shop Boys to Donna Summer, Aretha Franklin, Mariah Carey. And Mariah in 1993 was another big one for me. That was the first time that a singer came into studio to re-sing a record. That changed the whole idea of what remixing was. That was nothing like the original.

That was quite unheard of at that time.

And nobody heard Mariah Carey sing like that. They heard Mariah Carey the pop singer, but now they’d hear Mariah Carey wailing and giving it to the dancefloor.

So you basically asked her to come down to the studio to redo it?

They asked me to remix „Dreamlover“ and I’m like „I can’t flip this original. I can’t.“ I was saying this is the only way it can happen and I just threw it out there! I’d never produced a singer before. Nevermind, it’s Mariah Carey, the new queen on the block. I didn’t even think it would happen. I was like, okay, she will be singing and you’ll have to come up with a track. Okay. Alright. She was 21 years old at the time. And it was huge. It was bigger in the UK than it was in America. I mean in America it was people like Junior Vasquez at the Sound Factory, he was pumping that fucking thing for days. It was a whole another thing.

How did you divide the remix requests at Def Mix? Were the requests directed to both of you or individually?

Individually. Because Frankie had his own sound and I had the Red Zone bit. And Frankie had a scene and I had mine. People were telling Judy who they think should get it. We got requests individually. We did a lot of big names at the time. And I even turned down a lot of big names! I didn’t do it just to do it. I remember when the Rolling Stones, their company, were asking me to mix one of their records, I don’t know which one it was at the time, and they said „Can you send us a discography?“ And I’m like „Fuck, I do not send a discography. If you’re coming to me, you got to know what I’m doing, otherwise why do you even ask me?“ And then, as you move on, the Grammys were a big experience. Something I used to watch on TV. I went three times. But the first time I went, I was a producer with Mariah Carey, because I did „Fantasy“. The reproduction went on the album. At that time when it came to the Grammys, all the producers that worked on the album were with her at the Grammys. Dave Hall, some of the top R&B guys at that time. Anyway, Alanis Morissette had won the Grammy. For „Jagged Little Pill“. And I remember I’m in the middle row, maybe third row from the front, surrounded by all these people. I swear to god it happened like in five seconds. You hear the nominations, „And the Grammy goes to..“ and all I know was that we were not getting up. It was Alanis Morissette and I was like „Oh shit, no!“ and then the following year, or maybe a year later, they came up with the remix category. And of course me and Frankie were both nominated. And he got it that year. And then in the second year, I got it.

How did it evolve from there? Was that the heyday of Def Mix?

No, I feel that they came up with the remix category late. Because the remix category was happening really since the 80s. So I felt like it wasn’t the peak period because if it was happening at our peak period, we would have won multiple Grammys. For sure. And at that time I won it, I wasn’t even mixing that much anymore. I was more travelling as a DJ by that time. 1995 I actually got bored with remixing and I almost detached myself from remixing and I was travelling a lot. I was making money travelling.

Were you kind of tired of working in the studio so much?

It was that the first ten years of remixing you had different tempos. There were different rhythms. So it was more fun. When House mixes became famous, when everybody wanted a House mix, was when Steve Hurley remixed Michael Jackson’s „Remember The Time“. And in those days, it was called time-stretching. And there was like only one machine at that time that did time-stretching and it cost a thousand dollars and there weren’t that many of them. But „Remember The Time“ was such a hit record, it wasn’t even about the original, it was about the Steve Hurley mix, and after that what record companies always wanted was a House remix. The original concept of a remix in the old days was that you took the original and you extended it, but you kept the original parts. You just created an intro, a break, and an outro. But you used the original parts. Okay, maybe we added some keyboard parts. And then we added some percussion. But it was still the song of the original producer. Then it got to a point where we were just taking everything out and we were just keeping the vocals. So in reality, we’re re-writing a record. On the musical side, I mean. Because we’re adding whole new music. When it came to „Mr. Loverman“, there I re-did the whole track, everything. I got no writers and I got no production credits. The original writers and producers, they’re the ones that went running to the bank. And the original producers had nothing to do with what I actually did. Same thing with „Dreamlover“. Same thing with „Finally“ by Ce Ce Peniston. That was another record. Same thing with Jamiroquai’s „Space Cowboy“. You listen to the original „Space Cowboy“ that’s on the album, the remix is nothing close to what the original on the album is. I took „Space Cowboy“, it was a great musical composition, but it wasn’t really a verse-chorus-verse-chorus kind of record.

It was more like a jam.

Yeah, it was a jam. So I made this thing into a song. So the thing was that after a while everybody wanted the boom-boom-boom and it got to a point. Stevie V’s „Dirty Cash“ was another one where I changed everything, and there’s other people running to the bank. And it insulted me that when they worked on a future album that they didn’t bring me back and say „Hey, come work with us and be part of the next project.“ I really got fed up with creating hits for people. It just wasn’t fair. And doing the same beat every single day…

It was too one-dimensional?

It became too one-dimensional, yeah. I’d rather make my own music for that, than to keep doing the same. Even though this is what it is today, but at that time it was different. It was nice when I was mixing records at a 100 beats per minute. It was interesting, the next one was at 110 bpm. The other one was at 120 bpm. When I was making two or three records a week, that’s what made it interesting. And like I said, I had to draw a line to stop giving my ideas away. And when you’re mixing records and they’re selling millions of copies, and you got a one time fee. It’s one thing when you’re starting, but I had to draw the line. And at that time, in the mid 90s, travelling, DJing, touring – that compensated.

So you were not depending on it anymore and you lost interest?

Yes I did, I did. It was good to take a time off. And I still did some mixes here and there, but more things that I had to be into. Like Toni Braxton, it was nice to go to the studio with Toni Braxton, Julio Iglesias, U2. And it’s funny because I worked with all these incredible singers. I worked with everybody. I did some stupid records like „Needin’ U“ in my studio. I put in like three hours and I took two old records that I really liked and used to play back in the day and I just did the same out of a sample. And in those days there was no digital, so whenever we made something to play, we used to have so-called lacquers.

Reference discs?

Reference discs. Everytime you played it, it wore down. So anyway, I started playing this „Needin’ U“ in clubs and people used to be like „What is this record?“ „This is killer, this is killer! You have to put this out!“ I was like „This is some sample shit I fucking slapped together“ And I thought no, I can’t play that. I worked with Mariah Carey, I did fucking this, this, this. I did that Reggaeton sound, that whole Jamaican dance. I did that shit on my first album which was way ahead of its time. And I remember doing two videos, 100.000 Dollars each budget for both of those videos, they make it anyway. Here I do this Ibiza video for like 11.000 Dollars „Needin’ U“ and it was like the biggest fucking thing! I did this album, I spent 225.000 Dollars, I worked with Sly & Robbie, I got some incredible singers, I had Anastacia. She sang on my first album. And here I do this stupid fucking sample record and people were like „Woah, it’s amazing“, the best thing in the fucking world.

At that time in late Nineties, early Noughties, were you kind of losing interest in House anyway? Or was it kind of like an up and down thing, cyclical development or was it just going along?

I was just going along and I was busy touring. I was just busy touring and making a lot of money touring. Come the summertime alone, and even now it’s difficult to make music. I mean, now I walk on with my studio, I have my keyboard over there so now I could, because with the new technology I am able to create now. And it wasn’t until the new technology really took off that I was inspired to get back into things. I was old school, you went into the studio that was multi-tracks, all these things that you couldn’t take on the road with you and you needed to pay people to do these things. Now with the technology, the internet, Ableton, ProTools, all this, you can make whatever you want. So my studio is always with me. I still have a big studio in New York, I still use an engineer but I’m always in studio mode.

I have read you produce a lot with Ableton.

I love Ableton. I live on Ableton. It’s my best friend. My best friend for creating mash-ups. If I get a record, maybe I only need a part of it. I’ll take the best part, I’ll add jams, I’ll create things. In the old days when people hired a guy from New York to play in the world, it’s because you brought a sound. And they can hear that sound, they heard you play that sound. And the record stores were only over there. London has record stores, Italy, maybe Germany, maybe one store in France, but that was it. But everywhere across the world people hired you because you had a sound and they wanted that. They didn’t want to hear anything commercial. It got to a point, even when I was playing in one of the most underground clubs in Italy, it doesn’t matter that Ce Ce Peniston was a big record that I mixed, they know it, they don’t want to hear it. We want to hear some new shit! But now, today, because of the internet, everybody has access to Beatport, everybody has access to Traxsource, everybody has access to the same information. And now everything has changed with DJs becoming producers, so you have to bring something different. Your personality is your personality when you program records, but a lot of people now are playing their own stuff. I’m the last one that wants to play my old records, I want to play new stuff. But obviously people come up, they want to hear „Needin’ U“, it’s like, „But I have some new things!“ And you see all these big guys. They are producers, making their music. People want to sing along to those things. We’re talking about the big level market. I don’t want to play my old records. I don’t want to play these singalongs. I don’t want to play „How Would You Feel“. I don’t want to play „Dream“. For me one of those underground records that I’ve done that’s still underground is „I’ll Be Your Friend“ because it was never commercial, it’s like an underground classic. „Where Love Lives“ for example, and things. Because I was never into ProTools, I was never a computer geek. And I started with Ableton, editing, and once I got comfortable to edit with Ableton, it really inspired me a lot to get back into making music. That thing gave me so much rejuvenation. Because I can work it and I’m not a slave to other people. So when I want to go into the studio, if I get an idea, sometimes I need to hold onto the idea. Back home it was like okay now I have to do a studio session, I have to put all the moving parts into place to get it. So today I love it that I get records and instead of in the old days when you went to a fucking hotel, you went to a different country, there was no TV, nothing else instead of reading a book. And now I can sit down, listen, create some things.

You achieved more than many in your career so far, in your first forty years. What is there still to achieve? Do you still have a goal?

A goal, oh my god, if I could be like an ambassador to bring peace to the world, I would love to. I mean, just teach positivity because there is so much negativity going on out there. I’m doing this TV show in Italy that’s called „Top DJ“, it’s like the X-Factor for DJs and it’s just amazing how the culture has changed. And even if I have a lot to say, even if I don’t agree, because a DJ is a DJ and a producer is a producer. And I’m not saying that a DJ cannot produce. But because the technology has made it easy for people to do both. And I’m not saying do it both successfully. I’m happy to see what the genre of DJing has come to. The respect that DJs get. Even though it has evolved into something else, even though the new generation doesn’t respect or really knows how it got here. They have no clue. A lot of these kids never touched a turntable, never felt a piece of vinyl. They’re not growing up in the era where that’s what it is, that’s how you get to music. So I’m doing this show and you have some criticizing the show and the music. But I’m like „I’m not here to judge the music. I’m here to judge and to give opinion to the DJ.“ Because there is DJing and there is producing. I give them advice, and I have an opinion and judge them based on the technology part of things. To be better at it. To give them the criticism, what’s wrong and how you should go about it. I try to give the best advice that I can give to the next young DJ, because you got some stupid people that are DJing and are doing it for the wrong reasons and are making a lot of money and they’re getting paid and it’s a show. But there’s a lot of DJs out there that do have the passion. And they dream about playing in a club. And they dream about being this. And I was once one of them. So as a person that has been playing 40 years and has seen the whole spectrum of it evolve, and to still be a part of that spectrum – I’m not here to be bitter about it, because it has evolved. I was once one of the big guys, making the big money. I’m not that guy making the big money anymore, but I’m doing this because I love it. Not because I want to be a star, not because I want to play in a stadium, not because I want a private jet, not because I want to be a superstar. I didn’t wake up a superstar. The people give you that title. People wake you up a superstar. So I’m just here to give advice to the new DJs, I’m here to offer them the tools. And my advice on how they can be a better DJ. And that’s my position. Because I didn’t have that. But I can give that to somebody, as cruel as it may be. And today production is a big marketing aspect of every DJ – every DJ calls himself a producer even if he’s programming beats. Because they’re programming beats they think they’re a producer, but they don’t know how to work with vocalists, what about the songwriting, what about arrangement. But a lot of of the music that’s being played, none of that comes into play. There are a lot of grooves. And a lot of grooves are good! So I tell the new DJs take piano lessons, take musical lessons, it will make you a better DJ. You will hear tonality better, listen to different kinds of music. Let’s say the kid that’s only growing up with EDM doesn’t know anything more, I will say: „Listen!” If I hear a new DJ it’s my job to hear what this guy is about, it’s research, it’s just to understand. Because I sometimes need to be inspired. We all could use being inspired. And you know, I’m not up on everything. And also as a producer, I will hear somebody play something and be like „What was that?“ I hear an idea! It’s all about inspiration, opening up your ears, don’t be so close-minded. You can be a commercial DJ and maybe you need to grow up. If you only play EDM because they are the only DJs you know and you’re 17, 18 years old and you’re only listening to the radio. You’re not old enough to go to clubs, you’re not old enough to go around the world, you don’t have the access to hear these sets. So maybe I’ll say: If another guy comes into town, listen to him! Because when you hear different things like me, when I was a commercial DJ and I went to the Garage and I went to a raw House night, I was like „Wow“. I’m hearing something that I like and it’s expanding my horizons.

Special thanks to Cristina Plett for transcription.

This is a fabulous interview. Thanks for doing it.

WOW. Insane interview!

What a great interview. Hopefully after reading this interview many will be enlightened by David’s vast resume and his humble beginnings. There is a lot of knowledge and experience that David is sharing here.

What a very comprehensive and informative interview. I enjoyed reading this article and have a better insight of a truly, remarkable contributor and legend of the House and Remixing world. Big Up !!!

[…] published in Groove 161 (September/Oktober 2016). Interview by Finn Johannsen, transcribed by Cristina […]

[…] collective tastes have been a techno standard-bearer since it opened in 1989, and a historian by word and deed. He makes mixes prolifically — the set in question is a sequel to Twin Cities Mix No. 1, […]